|

David Newman - a 40 year career contents - Institution

of Electrical Engineers |

|||||||||||

|

________________________________ |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Aldermaston 1957-1962 |

Select an image to enlarge and zoom in

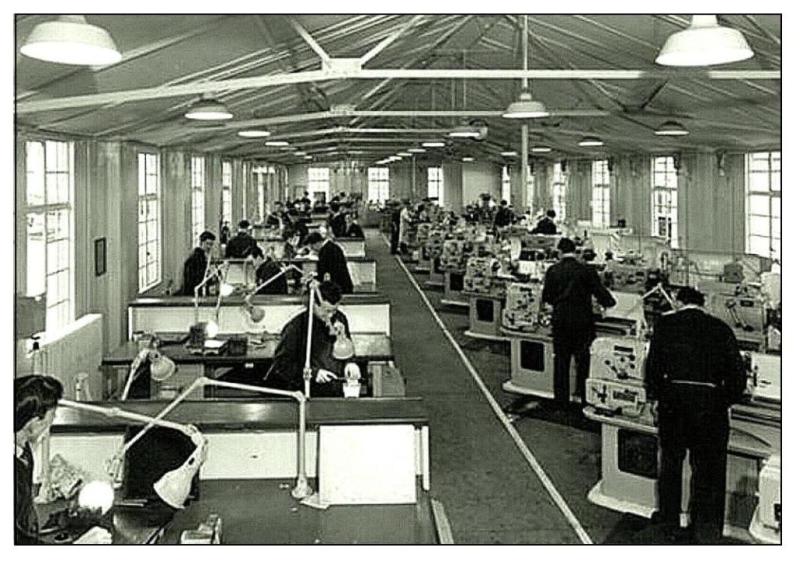

Apprentices school

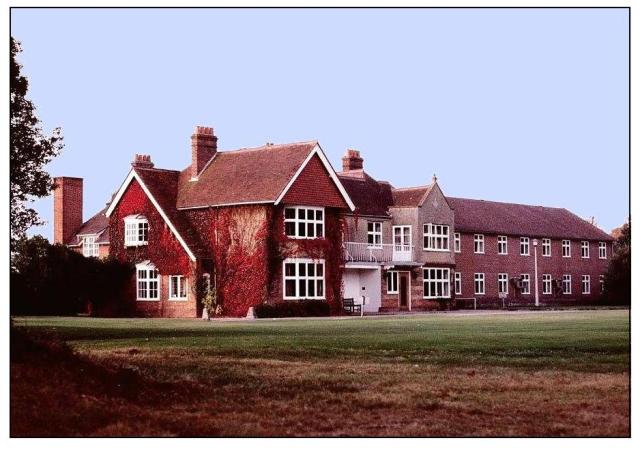

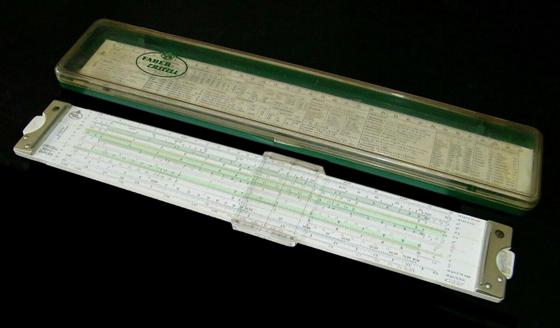

Blacknest Hostel Apprenticeship Brochure Prize day programme Sir John Cockroft presents prize all metal plane Slide rule prize Brief case prize |

|||||||||

|

DN

was accepted as a “craft apprentice” at the Atomic Weapons Research

Establishment, Aldermaston (now called AWE) and spent the first year in their mechanical

engineering apprentice’s school, while living in the fantastic Blacknest Apprentices hostel. At

the time a brand new electronics training facility was being built next to

the apprentice’s school at the time and I immediately volunteered to be in

its first year. During

the 5 years one moved around many engineering workshops, but never saw

nothing that look anything like a nuclear weapon! I did win two treasured

prizes however, one presented by Sir John

Cockcroft: a Faber Castell slide rule and a leather briefcase, both of

which I kept and used until they became yesterday’s technology. As I recall

it one prize was for machining an all metal woodwork’s plane. The

Nuclear Physics department designed and maintained portable radiation

measuring tools which contained the newly developed transistors. At the time

I was attending the Reading Technical College HNC course so asked the

lecturer if they were going to tweell us about transistors. His reply was “Oh

no, we know nothing about these recent devices. Where do you work?”! Towards

the end of the 5 years was offered a permanent position in a electronics

drawing office, but realised that this only involve drawing mechanical

aspects of a design and had no involvement in the Electronic design or

theory. Having expressed this to the bosses on completion of the 5-years was

appointed as an Assistant Experimental Officer and found myself working on a

new fusion research project called “Phoenix” under the direction of nuclear

physicist Dr. Donald Sweetman. After

just a year the whole team moved to the newly built Culham Laboratory near

Abingdon and DN moved with them. Dr. Sweetman later became the director of the Culham

laboratory. |

|||||||||||

|

|

________________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Culham Laboratory 1962-1965 |

||||||||||

|

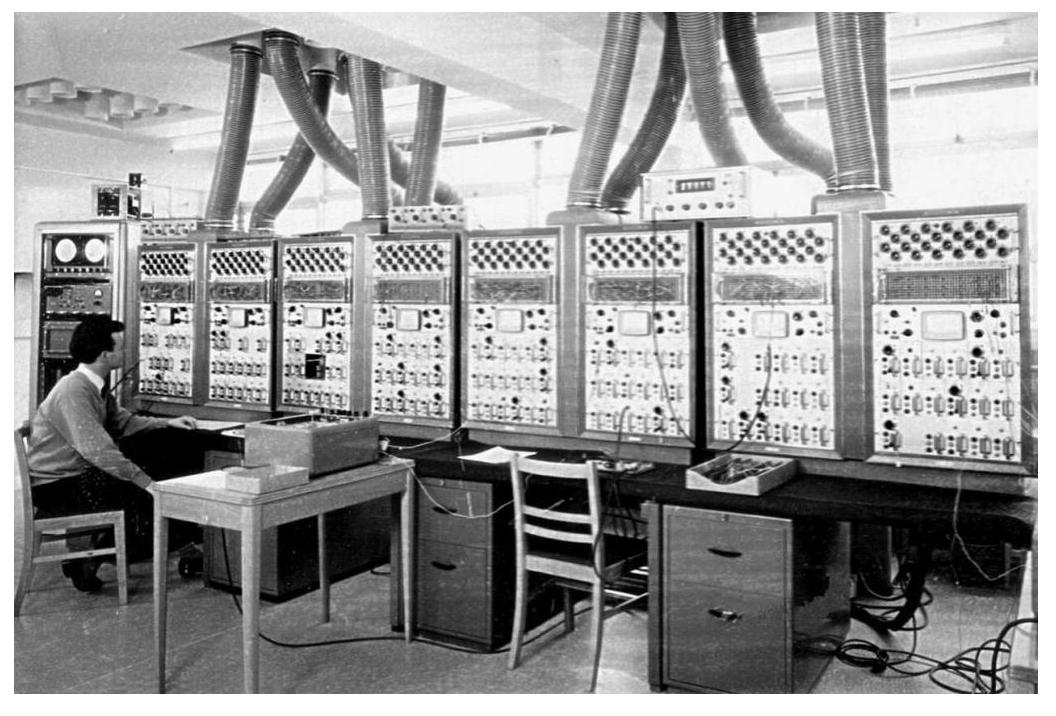

At

my first meeting with the head of Culham Laboratory’s Electronics Division I described the

15Kvolt amplifier I had recently built at Aldermaston at the request of my

boss in an attempt to stabilise the highly unstable plasma within the Phoenix

machine. He was highly sceptical about whether this simple one term feed-back

control system could even work and was also concerned about me working alone

on 15Kvolts. Having

helped re-assemble the Phoenix

project electronics equipment at Culham after the move I found myself

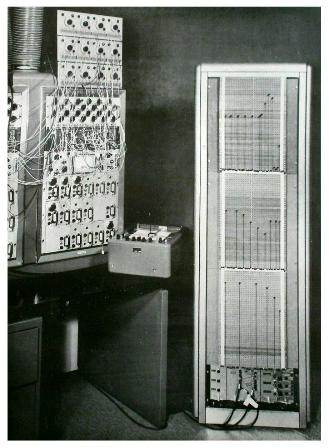

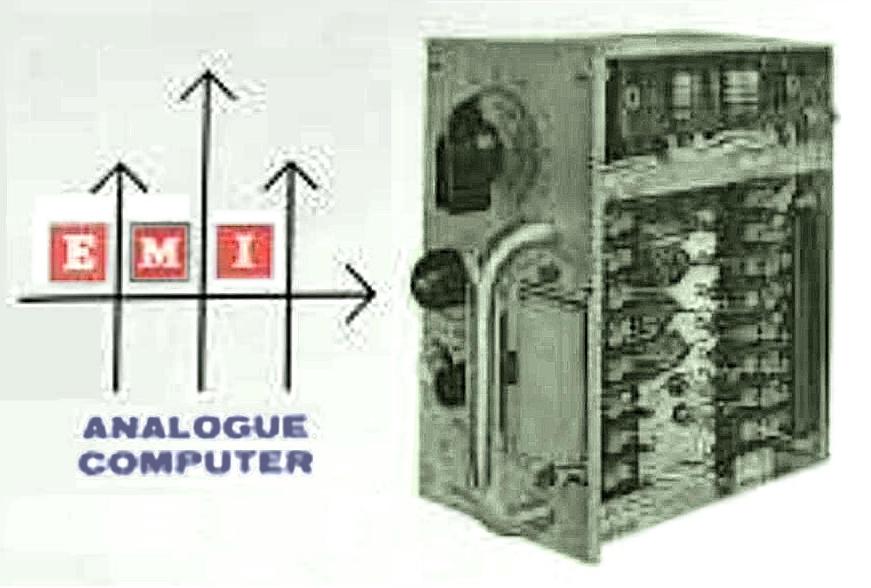

suddenly “invited” to work on Culham’s EMI

EMIAC” analogue computer which was by then based on elderly thermionic

valves and was used to solve electrical and nuclear physics dynamics problems

using differential equations. This involved having to learn about calculus

(which I have not learnt about at school) and complex Control Systems. One

assignment I was given was to build a special

function generator to be used on the analysis of satellite scans of the

Sun. The Culham based English Electric KDF-9

was used to spot check individual results and for this I needed to learn the

FORTRAN programming language, which was my first involvement with computer

programming. The KDF-9 mainframe computer was nowhere fast enough nor had the

capacity to carry out all the calculations required. The

satellite data came from UK rockets launched at Woomera, AU and a colleague

at Culham was assigned to attend these launches, I asked him if I could get

in one of these trips he said he would ask the ESRO guys. He came back with a

job application form which I complete and I was invited to Deft for an

interview and subsequently offered a job at ESTEC, Noordwijk in Holland. During

the Culham period I joined the British Institution of Radio Engineers as a

full Member (later becaming the Institution of Electronics and Radio

Engineers) as my HNC qualification did not enable one to join the prestigious

Institution of Electrical Engineers. |

DN using the EMIAC analogue computer function generator EMI

Function Module EMI valve

unit Culham

report the Culham English

Electric KDF-9 |

||||||||||

|

|

________________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

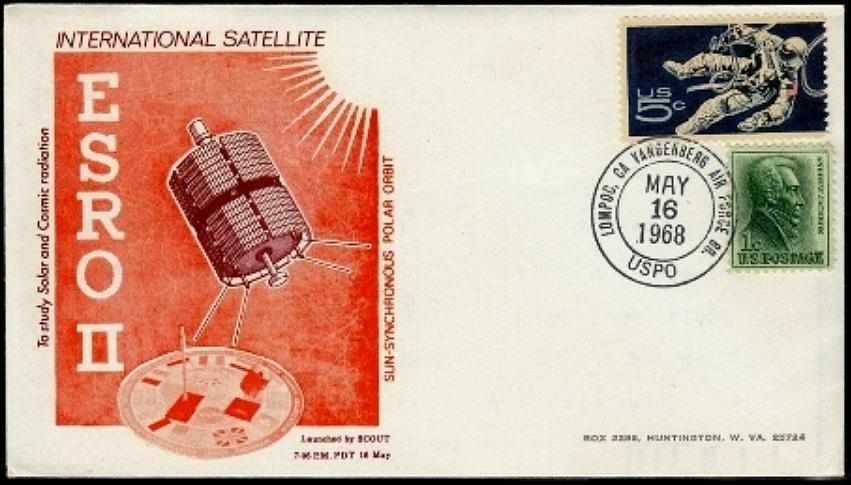

ESTEC, ESRO Noodwijk, Holland 1965-1969 |

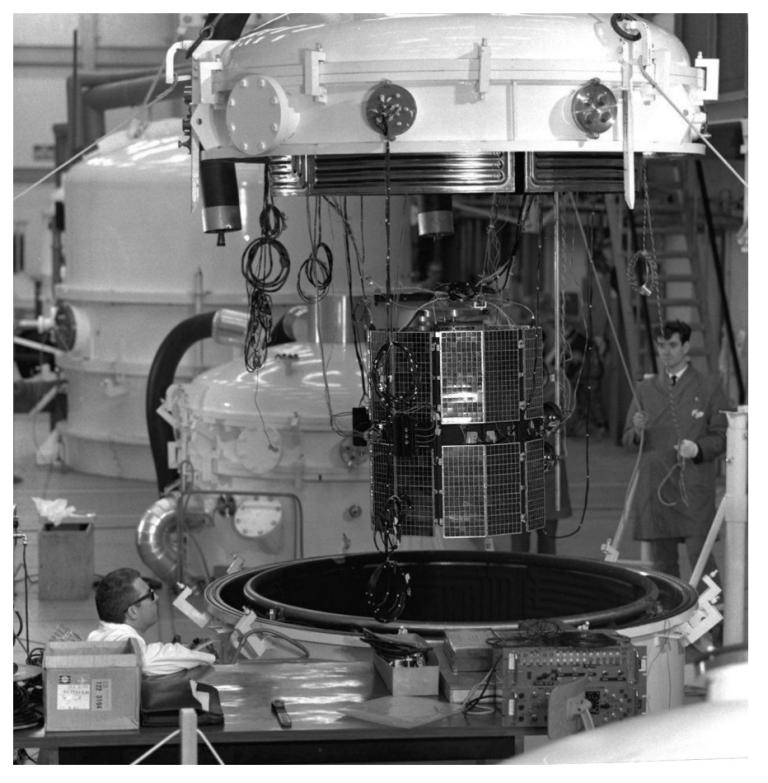

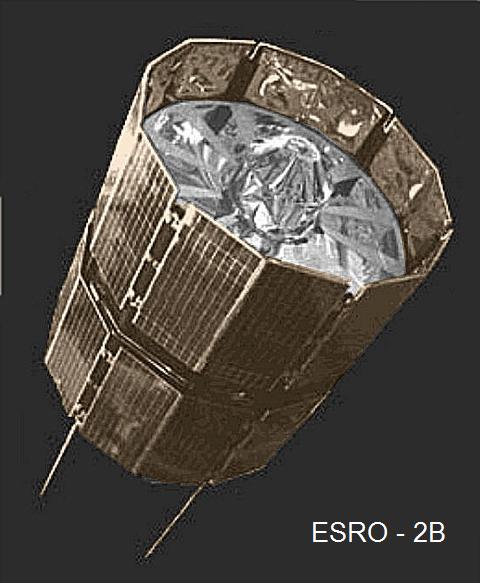

Checkout

Trailer at ESTEC

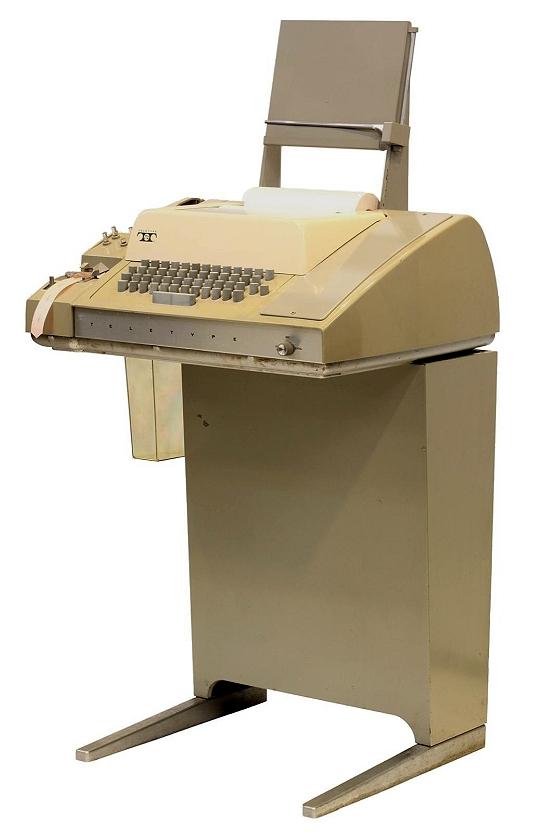

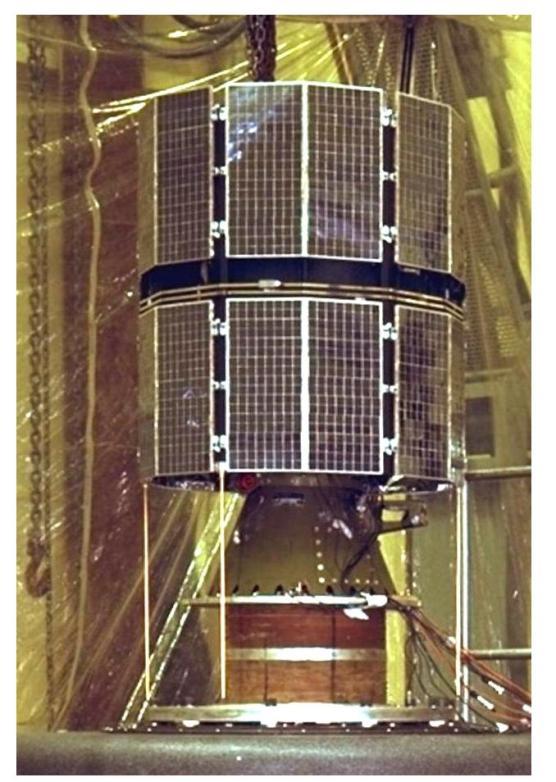

ASR-33 ESRO-II on test trailer saved from the fire chamber

testing ERO-II team at Vandemberg in

1967 launch from the

Scout rocket coloured logo on the

casing |

|||||||||

|

While

at ESTEC Noordwijk, I participated in the first ESRO launch

as a computer programmer in their Maths Division and worked on the “ground

checkout equipment” of the ESRO-2 satellite. This was being built by Hawker

Siddeley dynamics, in Stevenage (now part of British Aerospace). It had six

UK university experiments onboard (but no on-board processors) and happened

to be ready for launch well before ESRO-1, which was being built by a French

company. My

first task at Noordwijk was to organise the 3 phase wiring in the two

trailers! Then I could tackle the software in the Honeywell DDP-116 processor which was

in two 6ft racks with just 16K of magnetic core memory. All the

content of the memory was lost when the power was turned off and it had to be

re-loaded each day from 8-hole paper tap. Fortunately,

while I was at Stevenage when the satellite was being modified there were

long periods when the checkout equipment wasn’t needed, so I could work on

the software that had initially been supplied by a contractor. This was my

first opportunity to learn assembler programming. The compiler and loader

also had to loaded via paper tape, with new code having to typed on an ASR-33 teleprinter. The only output

was on a large heavy line printer that had a mercury column memory seen on

the left in the launch

sequence from the trailer GIF image. This

was my first experience of real-time programming as the processor and printer

had to keep up with telemetry data being continuously transmitted by the

satellite. While

at Stevenage the Noordwijk facility, which was still under construction, was burnt to the ground! However, the

second trailer which was located there was saved from the fire by the

staff, who were able to push it away from the burning buildings. In

1967 the team went

to the Vandenberg Air Force Base in California for the launch which used a

redundant Scout

DOD military launch vehicle. I was in the trailer on a hill side watching and

took a sequence of

photos, but sadly the launch rocket and satellite fell into the Pacific

when the fourth stage failed and we came home. A

year later however, in 1968, the team went back to Vandemberg taking the

back-up satellite ESRO-2B and on this occassion I was invited to sit in the

blockhouse with the US Airforce generals and hold down the “Ready for Launch”

button while listening on head phone to the guys in the trailer. This time it

launched successfully and orbited the poles thousands of times to complete

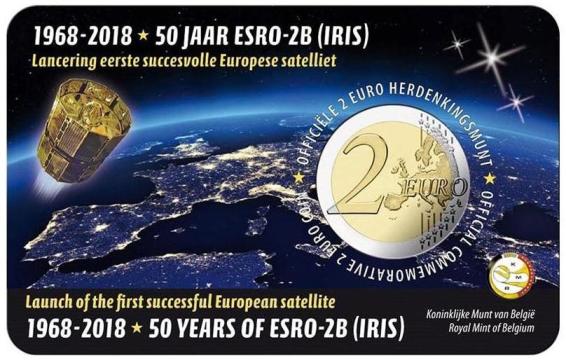

its research work. An experience that will never be forgotten. Here

is a European Space Agency

press release about ESRO-2 |

|||||||||||

|

space simulation 50 year celebration card 50 year coin |

The launch seen

from Checkout Trailer |

||||||||||

|

commemorative postcard |

|||||||||||

|

________________________________ |

|

||||||||||

|

|

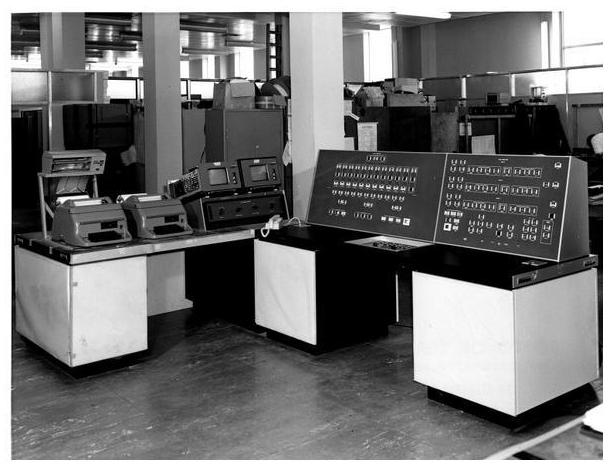

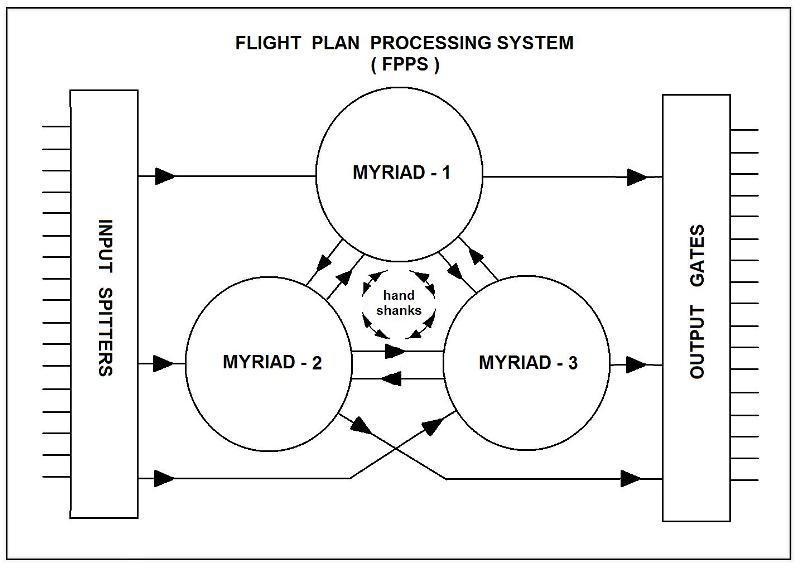

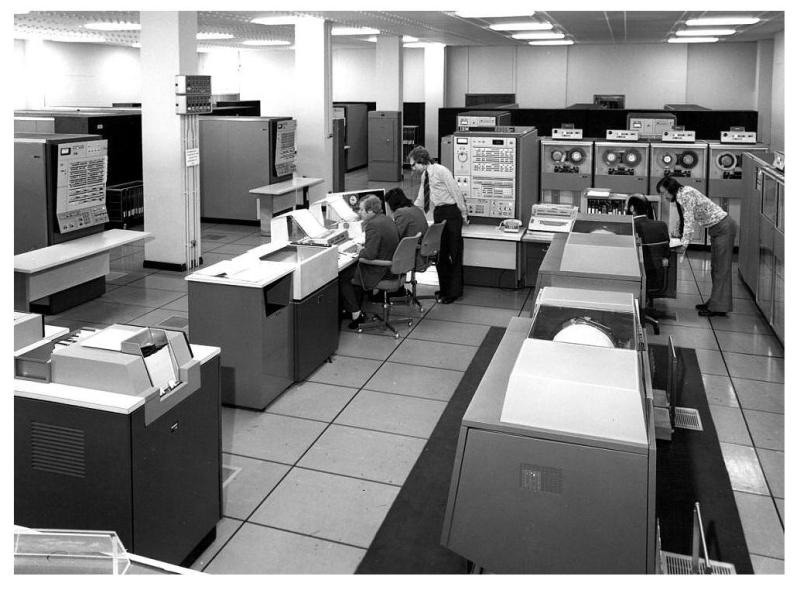

Marconi Radar, Great

Baddow, Chelmsford 1968-1972 |

Myriad at

Chelmsford Myriad at LATCC

triplicated FPPS diagram

IBM-9020 at LATCC |

|||||||||

|

I

joined Marconi Radar Ltd, at Great Baddow with the expectation of working on

graphics software projects, but was immediately placed with a team working on

an Air Traffic Control system for the London Air Traffic Control Centre

(LATCC), West Drayton. This was to be a real-time Flight Plan Processing

System (FPPS) presenting flight plan information on Visual Display Units

(VDU’s), which would replace the existing printed cardboard strips. The

requirement was that the displays were to be operated by the air traffic

controllers using an early form of “touch sensitive screen”. Apparently the

controllers did not wish to have to type on keyboards as they could then appear

to be no more than typists! It

was to be a highly reliable triplicated

computer system using three Marconi Myriad

machines which was new to everyone involved. Most of the software team

had no experience of real-time systems and having had previous real-time

assembler experience I was invited to join the small team working on the

software to handle the handshakes between the three CPUs. |

|||||||||||

|

The

contract was with the UK Board of Trade and Marconi were paid for the number

of lines of assembly code generated. This resulted that the management having

no interest in the programmers using subroutines, so they inevitably ran out of

memory and the system became too slow to handle the number of flights within

the south of England. When

system was finally handed over to the customers it was agreed that it could

only handle the amount of traffic in “middle airspace” which were mainly military

and non-commercial flights, and the recently created Civil Aviation Authority

decided that they had little choice but to purchase a proven IBM 9020 System

at a huge cost. Here is a New

Scientist article from 1972 about FPPS and the IBM 9020. After

FPPS was handed over to LATCC I was offered a position in the newly formed

CAA which was largely a merger between Department of Trade and Ministry of

Defence personnel. |

|||||||||||

|

|

________________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Civil Aviation

Authority, London 1972-1979 |

Ferranti Apollo

the programmable VDU |

|||||||||

|

While

based in CAA house, Kingsway in London, I was assigned an ATC planning role

in National Air Traffic Services (NATS) and concentrating on proposed “small systems” at Bournemouth and

Prestwick airports. My Bournemouth role involved evaluating the new “state-of

the-art” Programmable Visual Display Units (VDUs), later to become known as

PCs, for their potential use in air traffic control. I undertook this role

with some enthusiasm using my previous experience with the European Space

Agency and the ill-fated Marconi Myriad system for West Drayton and was able

to produce a sort routine that worked within the VDU. |

|||||||||||

|

The

bosses in both London and Bournemouth were staggered to discover that a small

box on a desk could actually re-sort flight data simply by selecting a key on

the keyboard and I could also not believe how quickly it happened. The

Internet did not exist in those days. The concept had been demonstrated. Recollections

of the Prestwick involvement were intriguing. On the first visit to the

Control Centre one was shown the then operational Ferranti system used to

control the UK’s half of North Atlantic. It was by then an ancient Computer

and 20 or 30 years old. It was at least based on transistors and not

thermionic valves! But a major problem was inadequate dust filtering and

cooling (maybe it was the dunes). This resulted in the discreet component

printed circuit boards having to be regularly removed and washed in soapy

water and dried in a specially constructed dryer before they could be used

again. Here is a 1960s article

entitled: Air

Traffic Computer by Computer which

is about Prestwick ATC and Ferranti’s involvement. When

it came to creating the specification for a replacement system it was soon

recognised that the existing system used some sophisticated mathematics to

calculate Great-Circle routes and times. These times were also used by the

airlines for planning and to display the arrival times at airports. It

transpired that no one at Prestwick knew how it did it and there was no

software source-code available. Ferranti

were asked if they had the mathematical algorithms and the source code that

that had been used, but the PhD level mathematician who had written the code

had long since left. They did not have the source code either and had no idea

how it worked, so it was back-to-basics using consultants to produce the

maths algorithms for the calculations needed. The

CAA procured a Digital PDP-11 system to evaluate its potential for Prestwick

and produced some Fortran code on it as part of that evaluation, but my back

could no longer cope with the daily trains journeys so moved to the Ford

Motor Company Research Centre at Dunton. As

many Air Traffic Controllers were members of the British Computer Society the opportunity was taken to also

join in 1975. |

|||||||||||

|

|

________________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Ford Motor Company,

Dunton 1979-1995 |

||||||||||

|

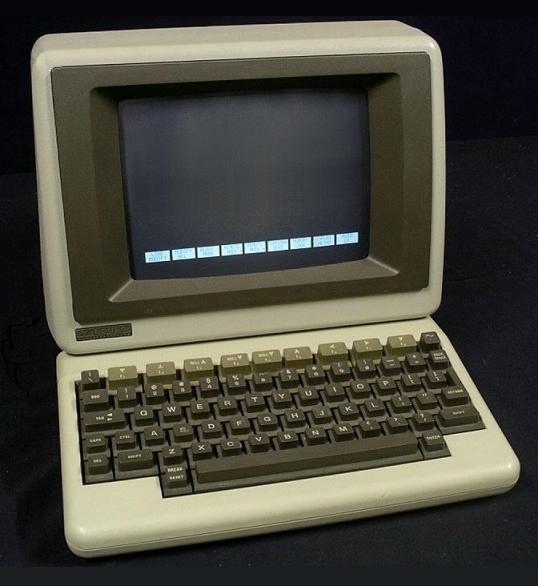

On

arrival at Dunton I was invited to work a new PDP-11 based project that was to be

installed in about 50 engine dynamometer cells, Each cell was to have a programmable VDU

fitted with function keys that the operator would use to store engine data,

edit and send to a communal printers. I soon learned that the Systems

Department at Dunton no experience of using a “mini-computer” in a real-time

environment or of using FORTRAN. Once

this project was up and running I was transferred to a new role as a

supervisor of a CDC mainframe

computer which they explained was to give me “management experience”.

During that period I party to about 20 data entry operators, who were using

punched cards, being assigned to other work as all the engineering staff were

encouraged to enter their own data using a PC. In

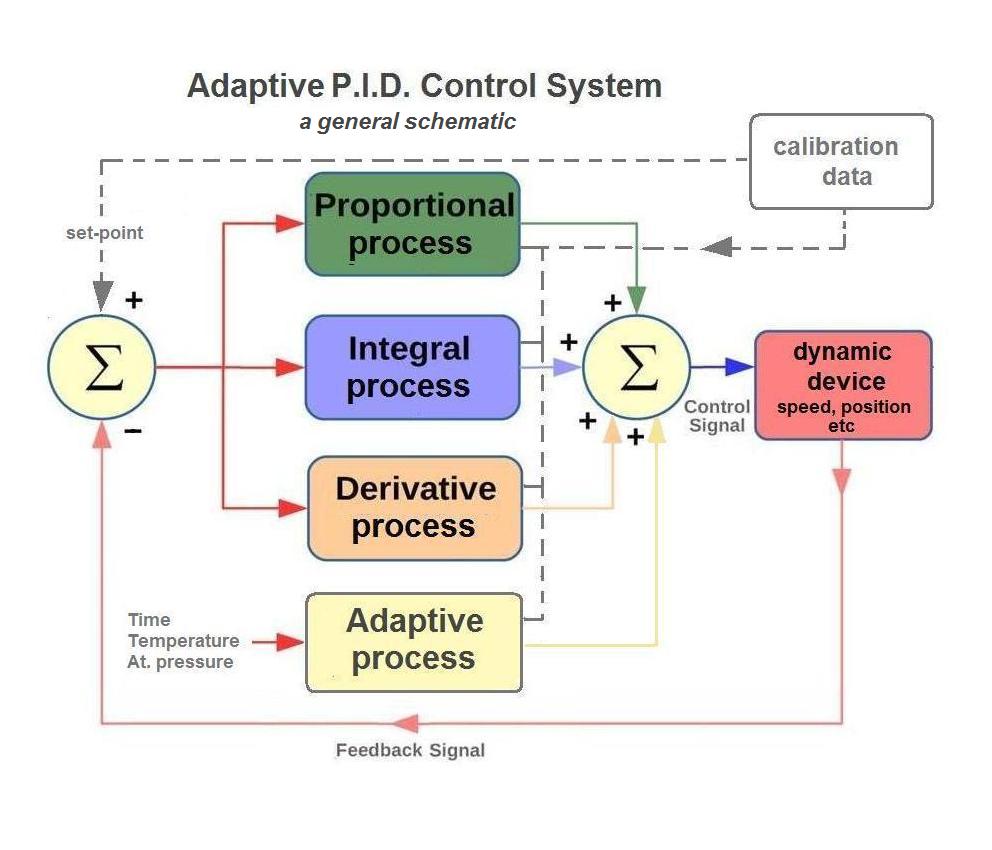

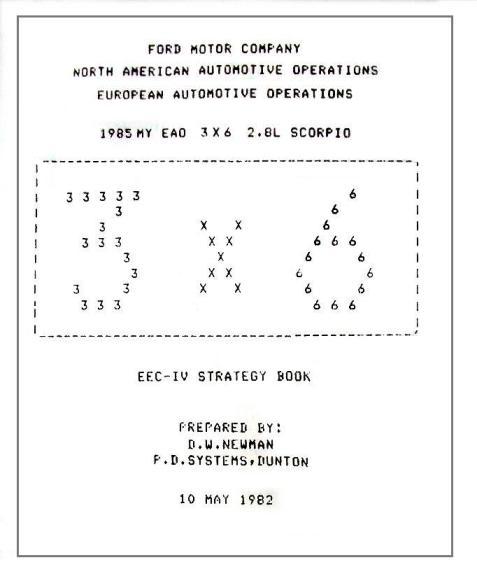

1982 Ford of Europe made its first in-road into using a microprocessor

in-vehicle for Engine Management, fuel injection and Idle Speed Control. Ford

in the USA had already been using these for several years to meet exhaust

emission standards which had not yet been adopted in Europe at that stage. The

first project in European was to use the Ford developed EEC-IV engine

management system to reduce fuel consumption on the six cylinder Ford

Scorpio by not injecting fuel into three of the cylinders when not needed

such as when idling. The project was called “3 x 6” and

initially involves spending considerable time at Dearborn, Detroit gaining

the experience of programming the EEC-IV in assembler. Ironically

the biggest challenge at that time was producing the software needed for idle

speed control which had the complex code used in the USA could not be adapted

for the smaller Ford-of-Europe engines without all of the emissions control

code as well, so it decided to produce a new version of the Adaptive PID controller for

the “3 x 6” and European use. Another

consequence of spending time at Dearborn was that I learnt about their

“Software Design Verification” (SWDV) process. This involved using a

mainframe computer to do a back-to-back comparison between the real-time

assembler code and an equivalent Fortran version executed on the mainframe.

The main motivation for doing this in the USA was to preserve evidence of

thorough testing of the software should any litigation arise associated with

exhaust emissions. We adopted this same advanced technique at Dunton which

later led to my involvement with the IEE and SCSC. Once

the USA style exhaust emission legislation had been introduced into Europe,

all vehicles needed fuel injection and an engine management system. Although

the EEC-IV system was largely a table driven system, which could be

calibrated for each engine and vehicle variant, the size of the software team

grew substantially and I was appointed supervisor. In

the mid 1980s Ford increasingly bought in from automotive suppliers other

in-vehicle systems such anti-lock brakes, central door locking, air-bags,

etc. which were based on microprocessors with software, and occasionally

there were doubts about the reliability of the software in them. Hence I

acquired the role of visiting these suppliers to quiz them about their

software design and testing methods, which was in some cases quite revealing.

|

PDP-11 CDC-6600 DN cartoon with engine electronics VDU with function keys Engine

management module Block

Diagram PID

controller diagram 3x6

strategy book cover Ford

publicity card DN on BBC TV

“Antenna” |

||||||||||

|

In

on more than one visit I uncovered that the code was produced by one young person

working alone with no formal training of programming or any previous

experience, who then simply handed a prototype module over to mechanical

engineers to be tested “on the road”!

So it became appropriate to describe the Ford testing technique for the

in-house engine management software and at that time had to make the point

that these was far less “safety critical” than the systems they were

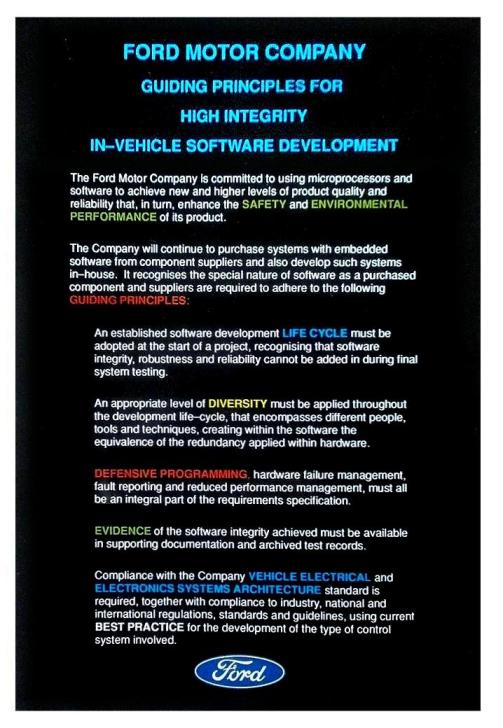

producing and something needed to change. One result was an A5 coloured Guiding Principles card

which was produced in conjunction with the Purchasing and Public Relations

offices and was sent to all the Ford suppliers. In

1987 Ford took over the Aston Martin Company and were offered engineering

support from Dunton. I was invited to go to Newport Pagnell to discuss how

they could use the Ford Engine management system and if special software

would be needed. I was amazed how basic their facilities were apart from the

workshop where vehicles were assembled there were just a few offices and

laboratories in an ancient building. There was a small electrical/electronic

lab which it seemed was home to just one electrical engineer. I

described the Ford EEC-IV system and the way it was “table driven” so the

main task for them was to calibrate their engines and vehicles by filling in

the tables using the EEC-IV tools that would be supplied. They went ahead and

no special software was needed. In

1988 I became a full Member of the IEE when IERE merges with the IEE and this

became key to my later IEE involvement. In

1989 Ford took over the Jaguar Cars and again I was invited to go to

Coventry, this time as part of a team, to share ideas about how the two

companies could work together. At that time, Jaguar bought in all the fuel

injection systems and other electronics from various European suppliers.

Again they were offered the Ford engine management system which they adopted. Their

Electronics Manager that I had discussion with however was more concerned

about the reliability of the software that they were purchasing from a range

of suppliers. We agreed in an ideal world there should be an industry-wide

standard to judge the quality and reliability for bought in products that

included software, as existed already for many other automotive components.

He suggested that we should jointly approach the Society of Manufacturers and

traders (SSMT) with a proposal that the automotive industry should begin work

on producing such a standard. The result was the SSMT contacted the Motor

Industry Research Association (MIRA) and wrote to all UK members of the SSMT.

A first meeting took place in 1991 at Nuneaton and it was agreed to create a

new The Motor Industry Software Reliability Association

(MISRA). In

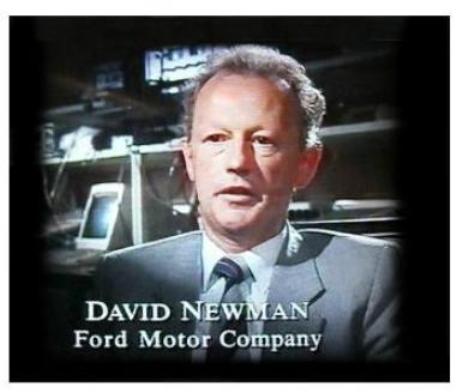

1990 with the blessing of the Public relations department DN took part in a

BBC TV Antenna programme discussing safety critical software. The

contribution was recorded at Dunton and a clip can be seen here... www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVpW8f8p70o

In

1995 and at the age of 55 I received an offered and accepted early retirement.

Part of the terms was that I would be offered contract/consultancy work with

a Ford partner and contacts with local charitable organisations needing

volunteer engineers, and I took up both offers. I was invited to make regular

visits to Jaguar in Coventry to help with their planning for ISO-9000

certification associated with in-vehicle systems with software included. At

the same time I was put in touch with the Chelmsford based charity Interact which helped disadvantage adults get back

into work by teaching them up-to-date I.T. skills. In my case it was mainly

helping them o use MS Word and Excel, and this I did one day a week for four

years. I also decided I should stand down

as Chairman of MISRA at this time as I no longer had the same role at Ford. |

|||||||||||

|

|

______________________________ |

||||||||||

|

|

Institution of Electrical

Engineers 1989-1997 |

The IEE

London building admitted as a

Fellow |

|||||||||

|

Ford

at Dunton were approached by the IEE to provide a representative to sit a newly

formed committee investigating standards for safety critical systems as they

had heard about our involvement with Software Design Verification. As it

happened there were virtually no full members of the IEE at Dunton as at that

time the vehicles only contained 12 volts and radios were bought in, so all

the engineers involved with the wiring layouts were mechanical engineers who

were members of IMechE. Have

joined the IEE committee I found that I was only member from the automotive

industry; the others being from aerospace, the military and the nuclear

industries. Having been

sponsored by members of this IEE committee, in 1991 I was appointed

Fellow of the IEE. This

IEE committee later became the foundation of the Safety Critical Systems

Club. |

|||||||||||

|

|

______________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Safety Critical Systems

Club 1991-1995 |

SCSC header and logo |

SCSC 30yr record |

||||||||

|

SCSC was sponsored by the Department

of Trade & Industry and the Science & Engineering Research Council,

and was supported by the British Computer Society and the Institution of

Electrical Engineers. DN

was invited to join the group because of FMC’s acknowledged involvement in

formal “Software Design Verification” techniques developed as part of meeting

USA exhaust emission regulations and later was invited to be its chairman. In

this period presented various

technical papers at their annual conferences and elsewhere about

automotive industries methods and plans for handling in-vehicle software. |

|||||||||||

|

|

______________________________ |

|

|||||||||

|

|

Motor Industry

Software Reliability Association 1989- 1995 |

||||||||||

|

As

a result of Ford taking over Jaguar I was invited to meet with the manager

of Jaguar Electronics division to discuss the potential to use the Ford

engine management system and software in their vehicles. Jaguar had only ever

used suppliers such as Locus and Bosch and had no means of judging the

quality aand reliability of their software. We agreed the industry needed a

standard to work to as it does with most other bought in components We agree

to do something about it and contacted the SMMT who in turn contacted all

their UK members. The result was a series of meetings at MIRA at Nuneaton in

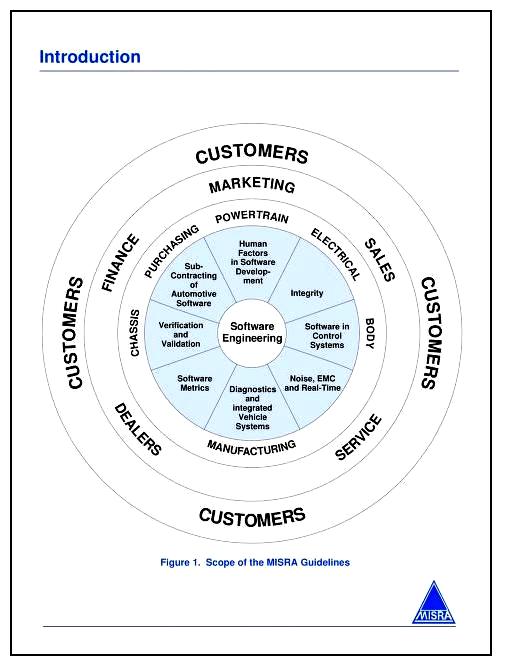

1991 and MISRA was formed. Here is an article entitled... What is MISRA? As

a founding member of this new group and with past experience of real-time

programming in other sectors, I was invited to become the first chairman. We

set a goal of producing guidelines specifically for the automotive sector,

having recognised that existing guidelines and standards used other sectors

such as the aerospace, military and nuclear that were much more advanced on

this subject. Also it would be inappropriate

to apply any of these standards to automotive engineering. With regular

weekly meetings planned, European based companies declined our offer to join

and attend, and Ford in Detroit declared I was already their representative. The

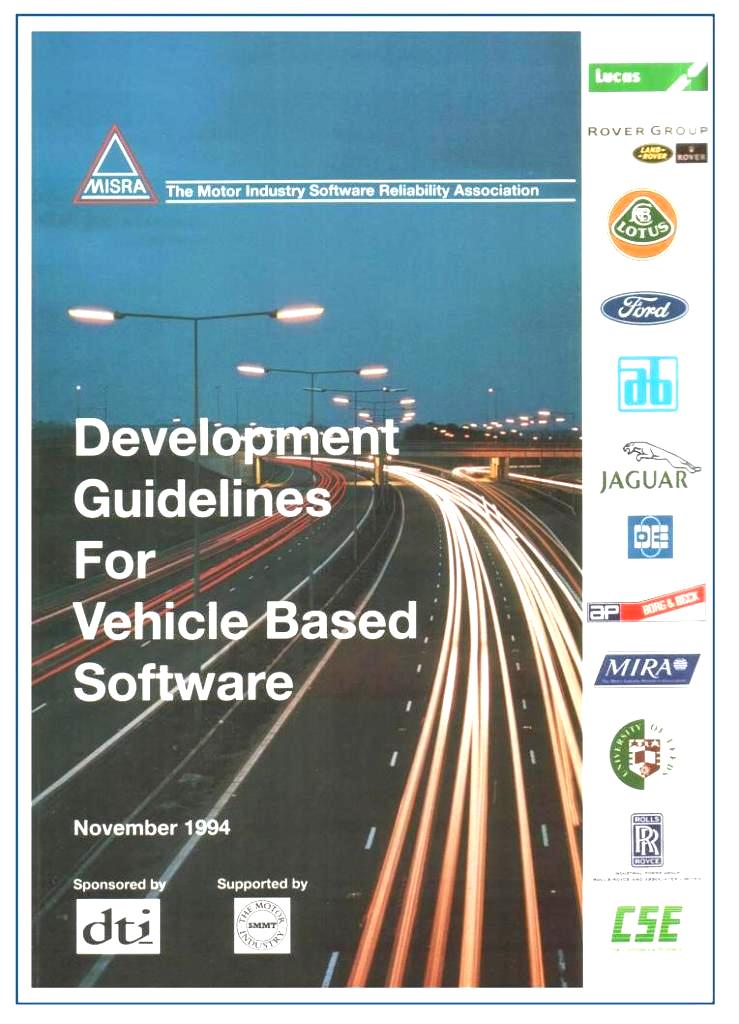

first edition of the MISRA guidelines were published in 1994 and work then

immediately began on producing associated guidelines for the C language.

Having taken early retirement from FMC in 1995, it was inappropriate to

continue as the MISRA chairman. The first version of the C language

guidelines were subsequently published in 1998. |

Computer

Weekly 1994 article MISRA

Guidelines scope of guidelines MISRA-C guidelines v1 |

||||||||||

|

|

______________________________ |

|

|||||||||