Smuggling in Goldhanger and the Blackwater

contents

o Smuggling around

the Blackwater

History of

Smuggling

Smuggling in the past is a

subject that attracts universal fascination stories about it have been heavily

romanticised and distorted. However, a wealth of factual information exists

from official records. Goldhanger has a particular historical interest

in the subject as the village is located in a prime position to have been part

of the Free Trade and the stories

that have been passed down, together with official records, confirm that the

village and the Blackwater were renown for being involved. The Coastguard

cottages, built in 1822, still stand as a lasting legacy to that involvement.

Much has been written about

smuggling and there are two primary sources of material: Collectors of Customs

were not only responsible for collection of revenue but were also responsible

for recording all smuggling activities, and were meticulous in their

documentation, which remains archived in county record offices. These reference

books used extensively this source of information and are quoted in the

article:

Smuggling in Essex, by

Graham Smith, 2005,

The Smugglers Century, by

Harvey Benham, 1986

Goldhanger - an

Estuary Village, by Maura Benham, in 1977

In contrast authors of

fictional works from the Victorian period onwards saw smuggling as an ideal

basis for adventurous, heroic, romantic stories. The violence involved was also

portrayed in these stories, such as in the semi-fictional History of

Margaret Catchpole. More surprisingly perhaps, the smuggling association

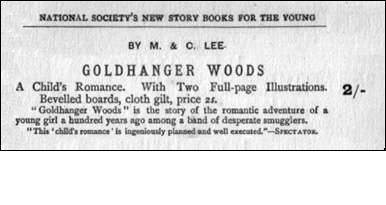

with violence was seen a suitable subject for children stories, such as in Goldhanger

Woods. These books are typical of this approach:

Mehalah, by Revd Baring Gould, 1880

Goldhanger Woods, by M & C Lee, 1887

Mistress of Broad Marsh, by Alfred Ludgater, (a

friend of Baring Gould)

History of Margaret Catchpole, by Revd Richard

Cobbold, Suffolk,1847

Cargo of eagles, Margery

Allingham 1966

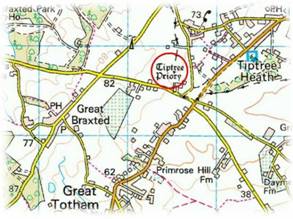

It is known that the

authors, Catherine & Mary Lee, had connections with, and stayed at Tiptree

Priory, which is on the edge of Heath which is well known for its association

with smuggling.

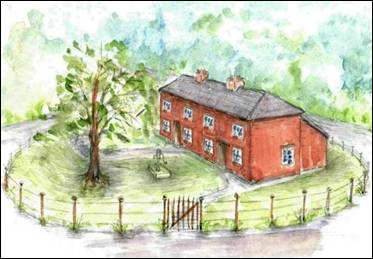

Tiptree Priory in the early

1900s

Although there are only a

few references in Goldhanger Woods to Goldhanger or indeed Tiptree,

there are several associations within the book:

o The `big house` in the book

is set on edge of a gorse covered common used by gypsies.

o Smugglers are known to have traded

on the common (see many references later to Tiptree Heath)

o "Goldhanger" is

referred to variously in the book as a village, and not just as a wood.

The complete book can now be read online within

Google Books at... Goldhanger Woods

online

Margery Allingham wrote her

last book entitled: Cargo of Eagles

in 1966 with a

smuggling/romantic theme: Detective, Albert Campion sets out to plumb the

secrets of Saltey, an ancient hamlet on the Essex marshes (said to be based on

Tollesbury). Once the haunt of smugglers, now it hides a secret rich and

mysterious enough to trap all who enter - and someone in the village is willing

to terrorise, murder and raise the very devil to keep that secret to

themselves. With the help of a love-lorn historian, and a one-woman avenging

army, Campion uncovers murder.

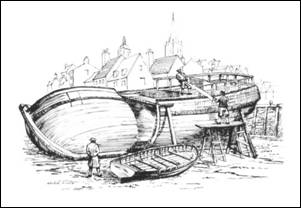

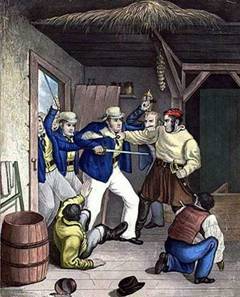

In the days before photography the adventurous image

of smuggling also made it a fertile territory for the artists of the time. . .

Smugglers Unloading

Contraband by George Morland

Moreover, there are an

abundance of paintings and drawings of revenue cutters, as revenue officers

were very enthusiastic about acquiring the latest and fastest vessels and were

equally keen to record them in artworks which can still be admired today. . .

Vigilant

Revenue Cutter on the Thames

In the past a surprising number of goods had excise

duty placed on them that resulted in these goods being smuggled, at over the

centuries they have included:

Imports: Alcohol and tobacco, salt, tea, coffee,

sugar,

nutmeg,

pepper, silk, lace, leather, soap, Bayes & Says (Baize & serge wool)

ship

parts: bowsprits, sails

Exports: wool & flour

Coastwise Traffic: coal, slate, marble, oysters,

salt

During wars and the immediate post-war periods many

rationed goods were also smuggled.

The relationship between

smugglers, the authorities and the public was always strained, and for various

reasons those in the rural areas appeared to have sided with the smugglers. . .

o Perhaps through poor

communications many people didn`t understand why goods were being taxed or for

purpose the money raised was being used for.

o At the time of the peak

smuggling activity there was very little government support for those in rural

areas, ie no welfare state, state pension, little road maintenance, sanitation,

etc.

o In fact, most of the money

raised was spent on fighting wars overseas and developing the colonies in the New World, so if ordinary people knew,

they probably would not agreed with it. Some of the major imports from land

acquisitions the New World such as tobacco and rum were subsequently heavily

taxed on import, with the consequential increase in smuggling.

o In the middle of the 15th

century laws was passed requiring all import and export goods to pass through a

small number of recognised ports that had a resident Revenue Officer. Maldon

was the only port in the Blackwater that qualified. Many workers in other

coastal locations resented their livelihood taken being away in this manner.

o Working people didnt have a

vote or have any other contact with authority and the law makers.

o Working class people werent

used to being taxed. There was no income tax or PAYE, purchase tax or VAT, as

in a cash and bartering oriented society the collecting and policing such taxes

was impossible. Taxing imported goods at a port was a practical solution for

the authorities and smuggling was effectively tax evasion and a direct

consequence. In the 1600s there was a Hearth

Tax and in the 1700s there was a Window Tax, but these only affected the

better off who had more than one hearth and more than six windows.

o In the later part of the

1600s a salt tax was introduced, with local Salt Officers appointed to collect

the tax and control salt production. This which substantially increased the

price of salt and led to much smuggling of salt around the coast and in the

blackwater.

see... Salt extraction in

the Blackwater

o Smuggling was classed as unpaid

tax by the authorities and a debt not a criminal offence so the police were not

involved.

o Most people, including the

poorly paid farm workers and fishermen, knew that a proportion of the fines

imposed was being shared amongst the revenue officers: "half for the king,

half for crew". Author Charles Lamb wrote: The "Honest Smuggler robs

nothing but the Revenue". Even parish churches were frequently used to

temporary storage of contraband, so priests, if not involved, "turned a

blind eye".

As excise duty and the

number of goods effected increased over the centuries, smuggling became an ever

increasing problem to the authorities, and the preventative measures,

organisations and legislation progressively evolved to keep up, but probably

always lagged behind the scale of the problem. In an attempt to control

smuggling stringent shipping laws were introduced over the centuries:

o

All imports & exports were required to pass through a recognised

port

o

Boat hovering close to the

shore became illegal

o

A Salt Tax and Salt Officers were imposed to control salt production

and collect the tax

o

A legal limit was set for the length of bowsprit to ensure Revenue

cutters were faster

o

No more than 4 oars to a boat permitted

o

Half a ship's crew had to be British

o

A licence was required for all vessels, only issued if the owner had

not been connect to smuggling

o

Lighting fires on the coast was made an offence

o

Smuggler's boats were impounded, burnt or cut in half...

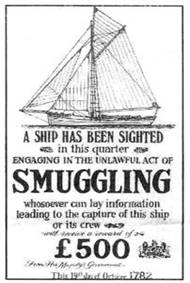

The authorities advertised rewards for information

that could lead to seizures...

The revenue men needed to be armed with the latest weapons and the swivel gun was state-of-the-art for the Kings Cutters....

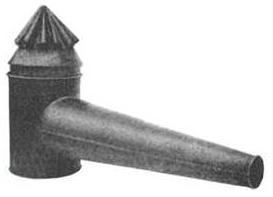

At the same time the smugglers developed their own

tools to help them avoid the revenue men, such as this special “Spout Lamp”

that only projected light in one direction and was used for discreet signalling

and “Spirit Bubbles” to measure alcohol strength in remote locations...

A Spout Lantern

Spirit Bubbles

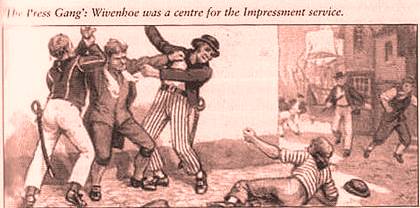

Smugglers caught at sea made

ideal impress candidates as they already had experience of the sea. Revenue

cutter crews were rewarded with 'head money'. The Impress Service, or more

commonly called the press gang, was employed to seize men for employment at sea

in British seaports. Impressment was used as far back as Elizabethan times when

this form of recruitment became a statute and later the Vagrancy Act 1597, men

of disrepute could be drafted into service. In 1703, an act limited the seizure

of men for naval service to those under 18, although apprentices were exempt

from being pressed. In 1740, the age was raised to 55. Impressment was last

used at the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815...

Smuggling on the East Coast

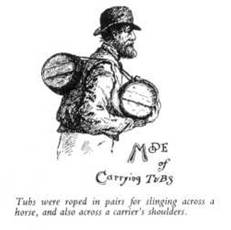

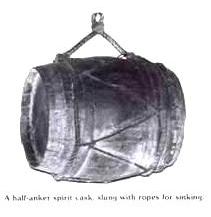

The pattern of landing and

distribution in England along the east coast changed over the centuries with

evolving policies of prevention. The Suffolk coastline was well-supplied with

good beaches which suited the open landing of contraband, a technique that

worked well in the 18th century, while the Preventives dozed in the distance,

or were open to bribes. As the net tightened in the early nineteenth century,

smuggling then intensified in the estuaries and creeks of the east coast, where

the activity was less easily observed, and where tubs, also called half-ankers,

could be secretly sunk in the murky waters, for later collection.

From the Chelmsford

Chronicle of 10 September 1779. . .

A correspondent informs us

that a few days since, a large smuggling vessel passed through Burnham river to

Hullbridge, where she unloaded her cargo; she mounted six carriage guns and 18

men, had on board 1,700 halves, and a large quantity of dry goods; since then

carts and horses have frequently been seen passing through Danbury, Chelmsford,

&c., loaded with goods. The Maldon custom house officers had a skirmish

with some of the smugglers, but they proved too strong for them. We hear one of

the smugglers is since dead from a wound he received in the skirmish.

Smuggling

was associated with violence

The length of Essex coastline, with many inlets and

estuaries and damp misty conditions meant it was ideal for smuggling goods to

and from the Low Countries. Also the Essex reputation for being a source of the

ague (malaria) kept both the authorities and the wealthy away.

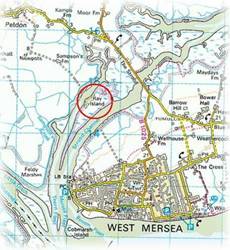

Smuggling around the Blackwater

An extract from the Maldon District Museum

Newsletter, Spring 2008...

As early as 1300, East Anglian wool was highly

prized was being exported and taxed. While it is usual to think of smuggling in

luxury goods from France, this British luxury was so desired that it was

frequently smuggled to France, and smuggling of this nature certainly occurred

in the Maldon district.

Fullbridge, Maldon

One, somewhat dubious, civic dignitary involved in

smuggling wool was Thomas Fumes who moved to Maldon in 1572. He became a

freeman of the town and from 1576-1585 was Head Burgess, then Alderman and

three times the borough bailiff.

He became involved with another bailiff and native

Maldonian clothier Thomas Clark and they were both accused of smuggling wool to

the Low Countries. Fumes was tenant of the Blue Boar where he appointed a

manager to run the inn while he traded as a bona fide wool factor to cover

their smuggling activities.

The Reverend Sabine

Baring-Gould, Rector of East Mersea from 1871-1881, chose Mersea Island and the

Blackwater as the setting for his classic novel "Mehalah"

which is based on smuggling and intrigue. The novel is set at the beginning of

the 19th. Century and uses names of people, places and buildings that still

exist to-day.

The Revd. Baring Gould...

In Mehalah we read:

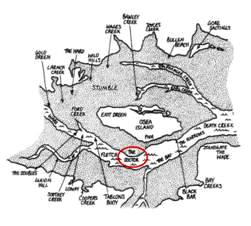

The mouth of the Blackwater was a great centre of

the smuggling trade: the number and intricacies of the channels made it a safe

harbour for those who lived on contraband traffic. It was easy for those who

knew the creeks to elude the revenue boats and every farm and tavern was ready

to give cellerage to run goods and harbour to smugglers. Between Mersea and the

Blackwater were several flat holms or islands...and between these, the winding

waterways formed a labyrinth which made pursuit difficult.

In addition to its

characters, Mehalah also provides the 20th century reader with a

romantic picture of the days of smuggling, when every inn had a false cellar

and coloured lights at night were an almost obligatory sight. A classic

portrayal of both Essex and 19th century life the novel was described at the

time as being 'as good as Wuthering Heights'. Fortunately the area which

Baring-Gould knew, and in which his characters spent their fascinating lives,

has evaded development . The Ray, where Mehalah the heroin lived, is now a

National Trust property and the Strood over which she went looking for

employment at the nearby Peldon Rose Inn, is still frequently subject to

flooding.

The Ray as seen from the

Strood today

The Revd Baring-Gould wrote:

"The villages of Virley and Salcott were the

chief landing places and there, horses and donkeys were kept in large numbers

for the conveyance of the spirits, wine, tobacco and silk to Tiptree Heath, the

scene of Boadicea's great battle with the legions of Suetonius, which was the

emporium of the trade. There, a constant fair or auction of contraband articles

went on, and thence they were distributed to Maldon, Colchester, Chelmsford or

even London. Tiptree Heath was a permanent camping ground of gipsies, and there

squatters ran up rude hovels; these were engaged in the distribution of goods

brought from the sea."

In 1975 BBC-East made a short programme about smuggling at

Salcott-cum-Virley in which the late Eustace King describes the smugglers

haunts and routes through the village, and showed and described the pond where

contraband was hidden. The pond had a "wooden bottom" so it could be

drained to recover the goods. In more recent years Eustace King became well

known to the residents of Goldhanger and other villages locally as the

undertaker, carpenter and sailor. The programme is now in the East Anglian Film Archive and can be

seen online at: http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/694 (3

minutes long)

Tiptree Heath was long known

as the notorious haunt of gypsies, fugitives from justice, squatters and

smugglers. It was reputed that smuggled goods were stored there in shallow

holes dug in the sandy soil and then covered with turf and brushwood.

Furthermore, smuggled goods were said to have been auctioned during Tiptree

Fair, which during the late 18th century was alleged to have lasted for a

month. Baring-Gould described Tiptree Heath as 'the emporium of the trade'.

Many 'safe' houses in the area were used for storage and the large brick

windmill at Tiptree was reputed used to hide contraband. A pond at Paternoster

Heath, Tolleshunt Knights, was used to conceal half-ankers of spirits. (Early

maps show that both Tiptree and Paternoster Heaths were once much larger areas

of heathland than they are today). It is said there was a tunnel from Tiptree

Priory all the way to Layer Marney Towers, which is a distance of about 7

miles, but perhaps it was a tunnel through the woods.

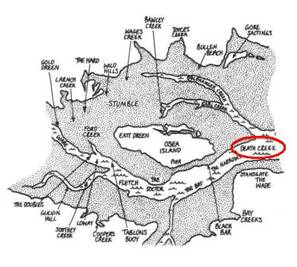

An extract an article in The

Daily Mail of 1977, written by James Wentworth Day. . .

My grandfather was one of those

that did in the Revenue men in their long boat one night more than 100 years

ago, an ancient fisherman and wild fowler confided to me. The Revenue men had a

watchboat, other side of the river by Stansgate Abbey, Wedgwood Benn's place.

Nearly all the fishing chaps from Maldon, Tollesbury, Mersea, Goldhanger,

Bradwell, Steeple and Mayland were in the Free Trade smuggling. Those Revenue

men were after them day and night. So one day. the smuggling boys held a

meeting in the Old Victory on Mersea island, and planned to do in the Revenue

chaps. They set a rumour that a big cargo was to be run ashore on the seaward

end of Osea In a creek they've called Death Creek ever since. Nobody knows what

did happen that dark night, but next morning they found the Customs long boat

drifting on the tide In the creek with 24 dead Revenue men aboard. And nobody

was ever caught. Those were the bad old days, we don't want murders again.

Death Creek has also been called Cut Throat

Creek and Deadman's Creek.

Smuggling at Goldhanger

The first known smuggling

activity at Goldhanger was in 1361 and that was the illegal export of wool,

carried out by 'Owlers'. In the past Goldhanger was sufficiently distant from

Maldon to escape the attentions of all but the most diligent officers stationed

there. A favourite early technique of Goldhanger smugglers was to float rafts

of tubs down the Blackwater, and land them close by at Mill Beach.

In 1898 in the book

entitled: Maldon & the River Blackwater, E A Fitch wrote of

Goldhanger:

One may hear several exciting smugglers tales from the older

inhabitants.

A local newspaper article in

1938 referring to Fish Street was entitles: A

reprieve for Street Smugglers

and text included this

phase: home for centuries of families of

East Coast smugglers.

In Goldhanger - an

Estuary Village, Maura Benham wrote. . .

As the marshes were thought to be

unhealthy there were few big houses and thus few magistrates resident near the

creeks. People living in Goldhanger have heard tales handed down of their

forebears turning a deaf ear to noises at night, and next morning finding their

horses lathered and a keg of brandy in the porch. They say the smugglers had a

depot at Chappel Farm and bound sacking round the wheels of the carts to dull

the sound and over the horses hooves to hide the footprints. The Chequers, the

only alehouse listed in Goldhanger in 1769, may have played a part. The goods

were often stored for a time, and there are stories of using cellars behind the

Chequers, or perhaps in a part of Goldhanger Hall whose whereabouts remain a

mystery.

A tunnel linking the

Chequers with the creek has also been rumoured, which seems unlikely today, but

Maura Benham also suggests that the Creek or a stream leading to it could once

have come very close to the Church. 'providing

a means to bring goods by water to the church, rectory and tithe barn'. We

also know that there was a much longer tunnel connecting the Blue Boar in

Maldon to the river near Beeliegh Abbey, so perhaps a tunnel behind The

Chequers could have existed, it could even have been a tunnel through the woods

to the Creek.

. ..

. ..

It is said there was a

passage or cellar under the Pitt Cottages that stood on the grass triangle

where the Little Totham Road joins the Maldon road (shown above), and that this

was used for smuggling. An Osborne's bus fell into a hole in the road behind

these cottages in the 1950s and this could have been the passage or cellar. It

was probably one reason why the cottages were demolished. Tiptree Heath was

said to be the 'sorting office', and it is said smugglers went from Fish Street

up Head Street, Blind Lane and Wash Lane, or landing in Joyces creek would

follow the green lane (on the west side of Joyces farmhouse) to Tolleshunt

Major to halt at the church, the Bell Inn or Renters Farm.

Joyces Creek

From Little Totham: The

Story of a small village . . .

It is said that smugglers

frequently used the route from Goldhanger along Blind Lane up Wash Lane, and

along School Road and The Street to Little Totham Plains and Tiptree Heath.

This route was probably used by smugglers carrying spirits, Bayes and Says

(baize and serge), wine and tobacco. Probably wool and sheep were taken in the

opposite direction. Tiptree Heath and Little Totham Plains were lonely, damp

and wild stretches of country, with a travelling population. These gypsies

worked in association with the smugglers with whom they conducted their

business.

In Smuggling in Essex published

in 2005 Graham Smith wrote. . .

Like most, if not all, villages

along the Blackwater estuary, Goldhanger acquired a smuggling reputation. The

village is about 3 miles to the east of Maldon at the head of a small creek and

was sufficiently distant and hidden away to escape the attention of those few

hard-pressed Customs officers stationed at Maldon. In 1939 Doreen Wallace in

Eastern England described it as 'a diminutive earthly paradise ... Tiny though

it is. . . a road heading seawards to nowhere. . . it is not to be missed. . '.

The village has hardly changed over the centuries, and the Chequers Inn on The

Square, listed as an ale house in 1769, was reputed to have been used for the

storage of smuggled goods in its cellars situated behind the inn.

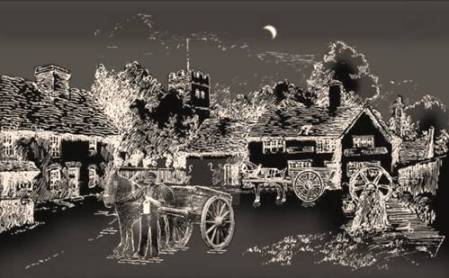

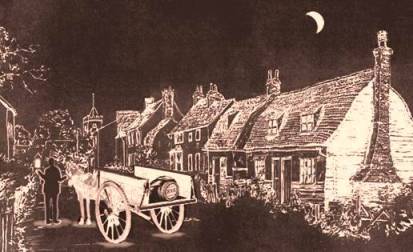

Movements through The Square

at night

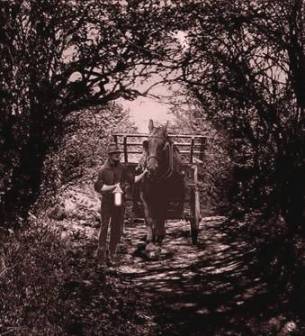

A tunnel-like footpath from

the Creek to the village

In an article entitled Smuggling on the Blackwater published

the East Anglian Magazine Vol XX (1960/1) Roger Frith relates an interview he

had with George Stokes, 'a member of one Goldhanger's oldest families'. . .

In my great-grandmother's time,

she remembered smuggling a lot and my uncle, he lived down Wash Lane. He was a

farmer by the name of Quy... Smugglers, they used ter go up Blind Lane into

Wash Lane and then up to Witham. Or Green Lane, down on the beach, up there,

through Longwick Farm to Tolleshunt Major, either to the church [St Nicholas

overlooking the Blackwater estuary]. The Bell Inn or Retner's Farm. Up Joyces

Creek they'd come and land their Hollands, lace and tobacco and shove the bandy

down cellars at Joyce s Farm. At night my mother used ter tell me they'd ride

up Fish Street carrying brandy on horses whose hooves had been covered with

cloth. But them days has gone. They went about forty years ago with the

fishing.

Well one night someone—he never

found out who—put 20 barrels of brandy in his shed and in the morning it was

found by the Customs. They took him off to the police station but by the time

they got it there, there were only 19 barrels left. He was taken to Chelmsford

Prison, and shoved into a detention cell, although he was quite innocent of the

fact of smuggling. During the time he was there a lunch consisting or either a

partridge or a pheasant was sent to him every day from outside and he never

knew where it came from. Smugglers used to go up Blind Lane into Wash Lane and

then up to Witham. Or Green Lane, down on the beach, up there, through Long

Wick Farm to Tolleshunt Major, either to the church, "The Bell Inn",

or Rentner's Farm. Up Joyce's Creek they'd come and land their Hollands, lace,

and tobacco, and shove the brandy down into the cellars at Joyce's Farm, or

Cobb's.

At night, my mother used to tell

me, they'd ride up Fish Street carrying brandy on horses whose hooves had been

covered with cloth. But them days has gone, they went out about 40 years ago

with the fishing. They're all buried now like my grandfather's stuff under the

gardens of Goldhanger Hall, which was pulled down, yes it's still there.

The Fish Street night run

It is interesting to note

that Stokes mentions Witham. There was a strong tradition that the Spread

Eagle, the town's celebrated coaching inn, had close ties with smuggling. It

was reputed that smuggled goods were stored in a secret well, which could only

be reached through a passage in the roof!

Goldhanger and the Blackwater

Estuary have long been connected with the production of sea salt (see. . . Salt

extraction in the Blackwater), and this trade has also been the

subject of smuggling in the past. Between 1693 and 1835 there was a salt tax in

place which substantially raised the price of domestic salt above its cost and

this led to the smuggling of salt.

A short extract from. . . The Salt Manufacturers

Association: salt tax

The salt tax on home produced

white salt was several times its market value and was twice that on foreign

salt. For fishery salt, the tax was greatly reduced and rock salt was taxed at

a lower rate than white salt.

By the 17th century salt-on-salt

refining developed by the Dutch was being practised by English coastal salt

works using cheap Cheshire grey rock salt and from the 1690s rock salt

refineries were being established to produce a purer white salt until an

extension of the Salt Act prohibited the further expansion of the trade. All

this resulted in the smuggling of salt and other forms of evasion of the salt

tax throughout the life of this tax and it is doubtful whether the revenue

earned justified the enormous cost involved in its administration.

The 1693 Salt Act created

the post of Salt Officer whose role

was similar to that of a Revenue Officer but was specifically to collect the

salt tax at source. Limits were also set on the number of salt processing

locations and in the Maldon area the only licensed site was at Heybridge. The

Heybridge Salt Works operated at Colliers Reach, near Heybridge Basin and much

later moved to Maldon and became the Maldon Crystal Salt Co., while the site in

Heybridge became Saltcote Maltings. As the north bank of the Blackwater Estuary

has been used for salt panning for centuries it is easy to see that smuggling

would have been rife, and isolated villages such as Goldhanger would have been

ideal for the movement smuggled salt along side other free trade items. As the fishery salt being used by the local

fishermen had a much lower tax and was readily available around the estuary,

presumably brought in by barge from Cheshire or France, this could relatively

easily be converted by salt-on-salt

processing in isolated locations. Although no records of illegal salt

production or salt smuggling in the village have been identified, it seems no

coincidence that the salt tax was repealed in 1825 and last recorded salt

production at Bounds Farm, Goldhanger was just a few years later in the 1830s.

There has been a more recent

example of smuggling at Goldhanger and in the Blackwater. At the beginning of

the 20th century, the brewer F H Charington, purchased Osea Island to used as resort for their landlords. It was

intended to be an isolated drying out

venue for those had excessively participated in the company's products.

Unfortunately, the resort did not operate for many years, one reason being that

the inmates continued to be regularly supplied with alcohol from The Chequers

at Goldhanger. Smugglers would row across to the island and tied bottles of

spirits to the Doctor's Buoy close to the island for later collection. The

Doctor's Buoy can still be found on navigation maps.

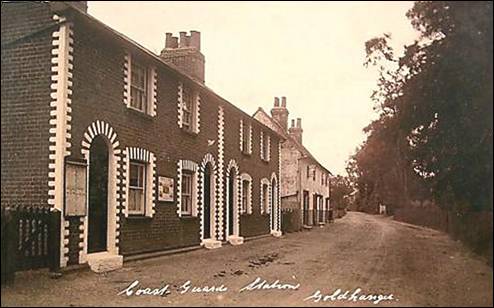

The Goldhanger Coastguards

The Coastguard Service was created in 1822 with the amalgamation of the Preventive Water Guard, the Revenue Cruisers and the Riding Officers, and in 1831 the Coast Blockade was also absorbed as all these departments duties overlapped. The Coastguard Service employed almost 6,700 men at the time of amalgamation. A modem Dictionary gives the definition of "Coastguard" as "An organisation with responsibility for watching coastal waters, to prevent smuggling, illegal fishing, to assist shipping, and for life saving". It is said that the everyday saying "is the coast clear?" originates from smuggling, meaning "are there any coastguards about?"

Once employed as a

coastguard it was necessary for an officer and his family to move away from

family roots to avoid any conflict of interest. However, until the familiar

blocks of Coastguard cottages were built during the second half of the

nineteenth century, coastguards and their families were accommodated in rented

houses in towns and villages round the coast. Hulks were also moored in the

creeks of Essex to accommodate the coastguard men with their families,although

not it seems at Goldhanger. They were known to been at Stansgate, Bradwell,

Burnham and Paglesham...

Watch Vessel “Kangaroo” at

Burnham

Watch Vessel “Frolic” at Stansgate

Watch Vessel 20 at

Burham

HMS Beagle hulk WV-7 at Paglesham (reconstruction)

The first reference to

coastguards in Goldhanger was in 1822. The details are in a book entitled

"A gin at Government House" which contain the memoirs of one

Agnes Stokes who was born in 1867. She related stories told by her mother of

her grandfather, a coastguard, who brought the family of nine children from

Walton-on-the-Naze to Goldhanger in a government cutter and a large sailing

vessel, which had a rough passage, which is a distance of about 25 miles around

the coast. They arrived late at night, and beds needed to be found for the nine

children in several houses. The Census returns of 1851 show a family headed by

Joseph Sherrells, 34 and his wife Alice, 26 and baby living in Fish Street,

giving his occupation as being boatman/coastguard.

By 1861 there were four

families whose head describe their occupation as the coastguard service, their

residence is only described as The Street

and was probably what is now 32 & 32A Fish St. The Census shows that in

1871 there were again four families who describe their head occupation as

"coastguards". Two families show their address as being Fish Street

while the others reside in Church Street. The Coastguard Service decreed that

officers could not operate in their own area and had to move away from home,

hence accommodation was needed close to their posting. Between 1867 and 1873

the Revd. H.F. Coape-Arnold from Warwickshire (not a Goldhanger Rector)

inherited land from Henry Coe Coape and build a pair of

redbrick cottages in Church street. The left-hand cottage in Church St. being

built as an armoury with adjoining internal doors. In 1875 he built another

pair of cottages to the right side making a terrace of four...

the Coastguard cottages with navy notice boards

outside the armoury of the Church St. block

In 1881 the Census still

shows four families living in Goldhanger who's head occupation is given as

coastguard, two still living in Fish street while the other two lived in Church

street, presumably in the newly built Coastguard Cottages. By 1891 there were

only three families whose head occupant were coastguards, and they all lived in

the Coastguard Cottages in Church Street. Today more that thirty coastguards

can be identified in www.genuki.org.uk/big/Coastguards as living in the

coastguard cottages at Goldhanger between 1850 and 1901.

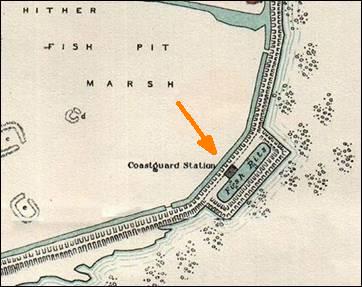

The coastguards maintained a

hut and flagstaff on the seawall near to Bounds Farm. The 1890s map on the left

below shows the Coastguard Station at the head of the Creek. Another 1980s map

in the centre below clearly shows the coastguard station on the seawall in the

same position as today's Sailing Club “starting hut” and adjacent to the

original Goldhanger saltworks site. the postcard photograph

from the 1920s shows the the hut with the flagstaff for communicating with

other coastguard stations on the Blackwater...

two 1890s maps with the huts

shown in different locations, and a 1920s photo of the coastguard hut on the

seawall

Here is an extract from a 1886 sale catalogue (ERO

D/F 63/1/10/6)

Bounds Farm, Goldhanger

Comprising farmhouse, farm buildings,

double tenement cottage with garden and bakehouse

and about 205 acres of arable and

pasture land. With plan.

Includes manuscript note that the Coast

Guard flag staff stands upon Lot 2 (Bounds Farm)

and the Government pays 10s. per annum

rent.

There is a shelter hut of the Coast

Guard for which they pay 6d per annum,

and the Fishermen agree to pay 5s. per annum for the use of the Pits and Drying ground on the foreshore.

John Veitch, Head Coastguard

stationed at Goldhanger in

1901

The coastguards on the

Blackwater and other Essex estuaries maintained an impressive fleet of high

speed cutters. Again, there is no record of any being permanently based at

Goldhanger, but we know they came here from reports of Goldhanger Regattas in the late 1800s. Cutters referred to

in those reports that took part in races were The Widgeon, The Fly and The

Rhine. Here are two images of coastguard cutters that were known to be based at

Bradwell...

|

|

|

|

excise cutter Fly based at Bradwell in the 1790s & 1800s, |

excise cutter Badger based at Bradwell, perhaps even earlier |

These cutters were renowned for apprehending smugglers in the

Blackwater, Colne, Crouch and Roach estuaries

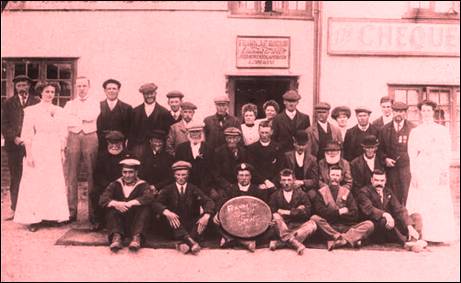

We do not know how well the

coastguards integrated to into village life, but the is at least one family of

descendants of a coastguard still in the village, and the picture of the

Friendly Brothers taken at The Chequers in 1910 shows possibly a coastguard

sitting in the group and could have been a member...

The Friendly Brothers in 1910

with possibly a coastguard in the group

The cottages have been much

modified since that time. Originally, the ground floor and upper floor provided

separate accommodation. The upper floor was reached by an external metal and wooden

veranda with a balustrade that ran along the rear wall, with an open staircase

at one end, which would have made the building look much more like military

barracks. The small piece of open ground at the southern end was a parade

ground, known then as The Court

(which today has a house built on it). The men would form up here at the

beginning of their duties and march at arms and with the flag down thought the

village to the coastguard hut on the seawall. This would have been a formidable

sight. No photograph of this activity have been found but similar scenes were

recorded at Tollesbury and Mersea.

Tollesbury Coastguards on

parade in 1900

Mersea Coastguards on parade in 1906

At the end of the Great War

the Coastguard Service was wound down, and in 1920 the Revd. H.F. Coape-Arnold,

who owned the Goldhanger Coastguard Cottages, put them up for auction and they

become private houses.