Public Health at Goldhanger in the past

CONTENTS

o

Public Health Facilities and

services

o

Benefits of the location and

Isolation

o

Other illnesses and Fatalities

o

Advances in public health

standards

o

Poverty

Background

“Public Health” is the term used to describe the well-being of a whole community rather than the individual, which includes monitoring and recording of the health of the community. From the Victorian era onwards there were great advances in medicine, public health, building standards, and sanitation. These changes had a huge influence on the health of the nation generally and would have had the same impact on this village, albeit some of the changes appear to have been slow in arriving. Since records began, life expectancy has steadily increased everywhere, and a study of past conditions in this village gives some understanding of why lives were so short in times gone by.

Locally published material referring specifically to the village has been used to learn about past conditions in the village:

o

Dr. Salter’s Diaries, complied by J.O.Thompson in

1936 (HS)

(Dr Salter was

the local medical officer of health from 1864-1933)

o

Goldhanger - an Estuary Village, by Maura Benham

in 1977 (MB)

o

Goldhanger Parish Magazines from 1895 to 1940 (PM)

Colchester

Library, Local Studies Section, ref: E.GOL.1

This has been complemented by additional information available from other sources:

o

Public Health in Gt Bowden in the mid 1800’s and beyond by Dr Paul Harrison (PH)

available from the Great Bowden

Historical Society, weblink…

www.greatbowden.freeserve.co.uk

o

The Terling Fever – 1867, by M.R. Langstone, 1984 (ML)

Essex library

Ref: E.TER.614.511

o

Tour through the Eastern Counties by Daniel Defoe in 1722 (DD)

o

Documents

held in the Essex Records Office (ERO)

o

Early

photographs taken in the village

o The internet

The earliest photographs available record

the condition of the housing in the village in about 1900. Its not know what

the conditions were like before these photos were taken, but they were unlikely

to have been better.

Tithe Awards listing (ERO)

for Goldhanger in 1820 indicate that most small cottages were tied or rented

properties, many with absent landlords. Some of the early photos clearly show a

very poor standard of construction and maintenance by today’s standards. The

presence of ivy, lichen, mould, and holes in walls, floors and roofs, resulted

in damp and very cold properties, and encouraged vermin(PH).

The Tithe Awards do not

identify children, so there is no sense of their numbers at the time from the

documents, but other genealogical data indicates that families of 12 and 17

were not uncommon in the village, so overcrowding in the small two-up, two-down

cottages must have been a major factor in transmission of diseases,

particularly amongst the children. (PH)

In 1918 Dr Salter recorded

in his diary(HS): “Attended a women with her 10th child, all of whom I have

brought into the world. Her mother was present as a nurse, who had 13 children,

all of whom I brought into the world. Her daughter was also present with her 2

children, also attended by me. A total of 25”.

Most cottages in Goldhanger

had no sanitation before the 1930s and the only safe fresh water for the

majority of residents was from the well and pump in The Square.

Several early photographs of cottages show signs of crumbling brickwork at ground level and holes in the plasterwork. Many had poorly maintained roofs and no gutters.

A well reported(ML) typhoid epidemic at Terling, Essex, in 1867 provides evidence of housing and sanitation conditions in the area at that time. Terling (pronounced locally as “Tarling”) is just 8 miles from Goldhanger, was (and still is) a similar size with about 900 residents, and is a similarly isolated village. The Terling Fever report describes “labourers cottages constructed merely of lath and plaster with thatched roofs in a great part of wood, often rotten and worm-eaten, with shallow wells often at a lower level than that of the neighbour’s “privies”.

"The wretched accommodation, which with few noble exceptions, was available throughout the agricultural districts of the county. The degradation and ruin of the miserable hovels called cottages, which the farm labourers have no alternative but to reside in, is beyond belief to all who have not eye witnessed, it is notorious that many of the noble Lord's Terling cottages are unfit for a pig to sleep in." The author of the report also found that a Royal Commission on housing standards in Essex conducted a few years after the 1867 epidemic did not identify Terling in a list of the worst villages in Essex.

In 1938 Maldon District Council condemned 23 cottages in the

Goldhanger as unfit for habitation and recommended their demolition.

Ironically many of these cottages were previously owned by the village Rectors and then passed on to their decendants who didn’t live in or near the village, so were “absent landlords”.

A temporary reprieve was granted in response to local opposition, and WW-2

deferred their demolition until the early 1950s. Then over 30 cottages were

pulled down and new council houses were built on the Maldon Road to provided

accommodation for the tenants who had lived in the cottages lost.

Public Health

Facilities and services in and around the Village

Until the 1930s, Goldhanger

had no mains water, sewage system or electricity, and hence no regular domestic

hot water source. There were no telephones until the early 1900s and hence no

emergency access to a doctor, the fire brigade or ambulance services. The

nearest doctor was located in Tolleshunt D’arcy, and Dr

Salter’s diary records a telephone was first installed in his house in

1908. Before the creation of a National Health Service patients paid their GP

directly for services, the doctor would probably have only visited the

wealthier patents at home, others would have had to travel to D’arcy to see

him, however sick they were.

The nearest hospital was St

Peters in Maldon, between (but before 1930 it was a workhouse), this would have

been an agonizing journey by horse and cart for the very sick. It is notable

that Dr Salter referred to: “isolation

tents up at Goldhanger for diphtheritic patents”, and the Terling Fever

report describes the installation of a temporary wooden“ Fever Hospital”.

Maldon Museum and ERO have photos of an isolation hospital at Broad Street

Green, Heybridge, with tents in the grounds. Originally located in a rural

location, Broomfield Hospital at Chelmsford was built as a TB isolation

hospital. There may also have been a small isolation hospital at Tiptree.

The use of temporary hospitals

were probably the result of both overcrowding in the small cottages, and the

need to isolate the sick from the healthy. Another benefit would be increased

exposure to fresh air, with greater oxygen content. However, as most epidemics

occurred in winter months, hypothermia probably also took its toll on patients

in these exposed environments.

Probably the only facility

directly related to public health in the village before the 1930s was the well

and pump in The Square to supply fresh safe drinkable water. The water from

this source was always said to be of quality good, except for a period in the

mid 1920s when the water table began to drop and it became necessary to dig new

well adjacent to the old one. The cause of this loss of water is said to be due

the large number of naval personnel stationed on Osea

Island at the later part of WW-1 using the underground water. A new well

was funded by a locally organised collection of £400, so even at that time the

local authority had not accepted any responsibility for the facility. All the

farmhouses and larger properties had private wells.

Mains electricity was first

installed in the village in 1937, a mains water supply followed, and finally a

sewage system. When electricity first became available refrigerators would not

have been generally affordable, and ice would have been carted from Maldon and

stored and sold by the butchers. The poorer residents would probably not have

been in a position to purchase ice.

Considering that

electricity, water and sewage had been installed progressively in towns across

the country from 1890 onwards, one wonders why it took until 1937 for these

services to reach the village. There are two possible reasons why mains

electricity was so late: Initially towns and cities had their own separate coal

and steam generators producing low voltage direct current (DC) of differing

standards, and it was inefficient to transmit this type of power any distance

over cables. A “national Grid”, using high voltage AC was only initiated in

1926 and took until 1937 to be completed across the country. The second reason

is that, rightly or wrongly, the Rector of the time the Revd. Gardner, was

strongly opposed to overhead cables being laid over his land and through the

village. This could also have delayed implementation for some years before it

was agreed that the much more expensive underground cables should be installed.

In hilly areas (but not

apparently at Terling) gravity provided the means to both distribute fresh

water and collect sewage through pipes, however in low lying flat regions

pumping is required. Towns and cities could afford coal fired steam pumps, but

rural areas had to wait for electricity to arrive.

Before the 1930s most

cottages relied on “night soil” collections from their privies, however the

farmhouses and larger properties had individual cesspits. In Tudor Britain

“Gong Farmer” was the term used for a person employed to remove human excrement

from privies and cesspits. Gong farmers were only allowed to work at night and

the waste they collected had to be taken outside city and town boundaries.

The Terling experience may

be typical of the region at that time:

“Although brick and wooden privies were built after the epidemic and

galvanised pails were provided to encourage more efficient disposal of their

contents, they were still empted on the gardens and allotments well Into the

twentieth century. This usually happened on Saturday night after dusk. Later

the night soil tanker made its rounds and when it arrived it was well to keep

doors and windows shut. For those who were lucky to have WCs the situation was

improved, but the effect on the river Ter was disastrous. It became a stagnant

cesspool as the supposedly clear effluent from the cesspools drained into it.

It was not until 1966 that Braintree District Council laid sewers throughout

the village to the small pumping station which it is pumped to the sewage works

in Hatfield Peverel.”

Before the streets were

tarmaced in the early part of the 20th century, there were probably

no surface rainwater drains or pipes in Goldhanger village, and a network of

ditches around the village leading to the creek would have provided drainage.

These would have been essential and effective in wet winter weather, but in

warmer drier times misused and contamination would have led to smell, insects

and vermin.

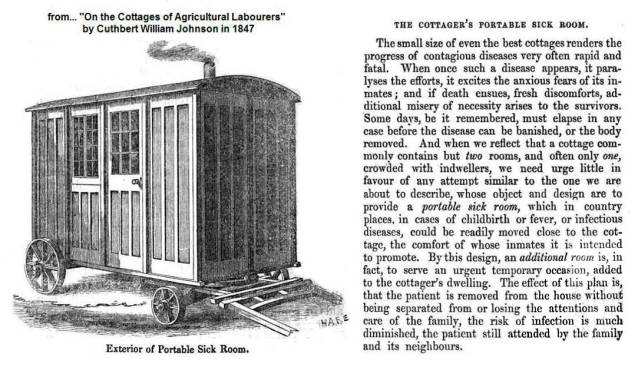

Ironically, it was a local man Cuthbert William Johnson (1799–1878), of

Heybridge who is famed for introducing many of the environmental health improvements

that we are familiar with today through the introduction of a major public

health legilation in 1848. His

association with the Heybridge salt works, which his father owned, led to a

passion for salt and its potential uses in agriculture and health. Both he and

his brother George were admitted to Grays Inn, and Cuthbert went on to help

bring about the passing of the Public Health Act of 1848.

Cuthbert Johnson was a

commissioner of the metropolitan sewers and he campaigned for the legislation which

resulted in the 1848 Public Health Acts. He resided at Waldronhurst, Croydon,

where for thirty years he was associated with the local board of health, which

pioneered a number of sanitary improvements under his chairmanship. His

knowledge of law was very valuable to the local board, which was involved in

extensive legal actions over matters of water rights and river pollution. He is

listed in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biographies (ref: odnb14871) and

amongst many other books and articles wrote:

The Advantages to Be Derived from the United

Application of Wilson's Baylis's Patents for the Manufacture of Salt from

Seawater, 1838

The farmer's encyclopædia, and dictionary of rural

affairs, 1842

On the Cottages of Agricultural Labourers, 1847

The Acts for Promoting the Public Health, 1848-1851

The Benefits of

the location and Isolation of village

The location and degree of

isolation of the village would have offered some defence from the transmission

of diseases that were prevalent in overcrowded towns and cities. Before the

days of public transport, most residents of the village would not have

travelled far, so catching an infection in a town and city while visiting would

not have been a frequent occurrence. Furthermore, the close proximity of tidal

salt water in the Estuary could be used for swimming,

washing and even effluent disposal.

The many small fresh water Glacial ponds in and near the village also had

benefits, these were used for animal drinking water and could have had other

uses such as water for washing clothes, etc. The availability of fresh food

from the local farms: meat, vegetables, fruit, milk, etc., and fresh fish from

the Estuary, which was stored temporarily in the Fish

Pits, would also have had significant

benefits that may not have been available all other villages.

Diseases and

Epidemics (in approx. chronological order of major epidemics)

Leprosy, St Giles Leper Hospital,

Spital Road, Maldon, was founded by Henry II in the twelfth century for the

relief of the inhabitants of Maldon and the surrounding district suffering from

Leprosy. The ruins of the buildings remain and are listed.

The

following in taken from… www.dartfordarchive.org.uk/medieval-

Lepers

Leprosy was a common disease

in medieval times and was thought to have been introduced into England as a

result of the Crusades. The epidemic was most severe in the thirteenth century.

Lepers were treated as outcasts from human society. Leper hospitals became a

prominent feature of town life; there were over 200 in England.

Although now identified as a

specific disease, in medieval times, leprosy was the name given to many skin

conditions including eczema, psoriasis, dermatitis, scabies, syphilis,

tuberculosis and smallpox. Lepers were forced to wear a distinctive style of

clothing consisting of a mantle and beaver-skin hat, or a green gown. In their

hand they carried a bell or clapper, through which they were to give warning of

their approach so that everyone could get out of the way in time.

Leper hospitals were known

as Spital Houses, [hence Spital Road in Maldon], or the Lazar House, after St

Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers. The segregation of lepers and those

suffering from other skin diseases in purpose-built hospices, away from the

rest of the community, was very effective in bringing about the eradication of

leprosy in England by the middle of the sixteenth century.

Black Death or Bubonic Plaque of 1348 “swept away half the clergy

of Essex and probably between a third and a half of the population”

(MB). At that time it was generally considered necessary to bury the dead well

outside the towns and villages, which has resulted in legacy of cemeteries and

chapels being located well away from village centres, as at Great and Little

Totham, and Tolleshunt Major. However, as the Goldhanger burial ground is in

the middle of the village, this may indicate that the disease was less severe

here.

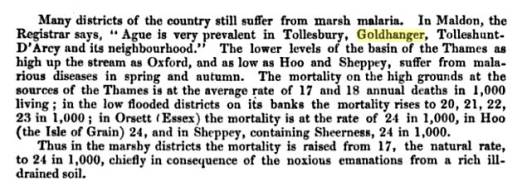

Ague now called Malaria is a disease transmitted by mosquitoes

that thrived in stagnant water in the fens and mashes and ponds and was prevalent

in Essex and along the Thames estuary until just after the First World War.

Daniel Defoe wrote about the Blackwater and Osea Island in the 1722 (DD) that

local men acquired “14 or 15 wives” because they were immune from the

effects of the damp and foggy marshes and the associated disease of Ague,

whereas their young wives “succumbed to the disease within a year or two”,

so the men went back to the “uplands” to find new wives to bring back to the

marshes. The progressive building of seawalls

over the centuries, mainly to benefit agriculture, had the side effect in this

region of reducing the mosquito population and hence the disease. Epidemics of

ague were always associated with warmer ambient temperatures.

In 1837 John Argent, Malster

of Goldhanger, churchwarden, “Overseer of the poor”, together with his family,

were removed from the village and conveyed to Glemsford in Suffolk by order of

the court. In manuscript papers preserved in ERO, references: Q/SBb 528/53/1,2&3

vague medical reasons are given but no specific illness is identified. It may

have been malaria.

From the Journal of the

Royal Statistical Society of 1857…

Cholera In 1866 Dr Salter “attended

a meeting of the local Cholera committee”.

Typhoid The 1867 outbreak on typhoid fever in the village of Terling has

been well researched and documented (ML). Terling is about 8 miles from

Goldhanger and was a similar size village with about 900 residents. 300 inhabitants

contracted the disease and 44 died. This unusual rural epidemic merited reports

in The Times and The Lancet at the time. Lack of clean water, poor sanitation

and poor housing were all blamed. Early deaths during the outbreak were mainly

amongst the women and girls, probably due to the males spending more time

outdoors or because they drank beer rather than water. Later on however, as the

men were obliged to spend more time at home looking after sick relatives they

too succumbed. Major typhoid epidemics ended in the UK around 1912.

Smallpox In 1871 Dr Salter was “busy vaccinating everyone in

consequence of an epidemic of smallpox” (HS).

In July 1884 Dr Salter was “Vaccinating like mad to stop

small-pox” and again in Aug 1884 “Vaccinating from calf at Tollesbury

all afternoon”. Smallpox epidemics appear to have ended in 1905.

Tetanus In 1882 Dr Salter wrote an article in the Practitioner

about a case of Tetanus in a 51 year old labourer. With the doctors recommended

medicines the patent made a full recovery and returned to work. There have been

other recorded incidents of Tetanus in the village, usually associated with

garden implements, but it is not known if these are exceptional.

Diphtheria In October 1883 the Epidemiological Society of London reported on

a diphtheria case in Goldhanger affecting two boys and one died. The report

claimed disease had been brought from Halstead in some needlework and a paper

bag used had been given to the boys to “cut up”. In 1890 Dr Salter wrote “Up to our necks in Diphtheria”.

In 1900 Dr Salter recorded that “isolation tents are up at Goldhanger for

diphtheritic patents” (HS). The need for tents was probably the result of

overcrowding of children in small cottages. A vaccine for diphtheria was

introduced in 1942.

Scarlet Fever there was an epidemic in winter of 1918.

Tuberculosis (Consumption) In Jan 1911 Dr Salter wrote

“Placed on the county committee for fighting consumption”.

Influenza There were epidemics in the summers of 1891,1905,1909 &1918.

Dr Salter made many references to influenza epidemics in his diary (HS) over

this period. Deaths from flu were not uncommon resulting from pneumonia.

Children and 20-30 year olds were most affected (PH).

Measles, Mumps, Rubella(German

measles), Whooping cough mainly affected children.

Schools were frequently closed in an attempt to contain the spread (PH).

Diarrhoea Baby & Infant deaths were often caused by bottle feeding

un-pasteurised cow’s milk (PH).

Bronchitis and Pneumonia in children was associated with

dark, damp mouldy overcrowded housing. However, by 1920 rural areas had lower

infant mortality rates generally than the towns due to the available of fresher

food (PH).

Other illnesses and Fatalities not related to epidemics

While Public Health is

primarily concerned with epidemics, other non-contagious chronic illnesses

would have had an equally serious impact on village life in the past.

Fifty five young men from

the village “took up arms” and participated in the Great

War and 17 were killed and are remembered on the war memorial. However,

many others returned home seriously injured and some were known to have

suffered from the effects of gas and shell-shock for the rest of their lives.

Army discharge papers were frequently marked “LMF” which is an abbreviation for

“Lack of Moral Fibre”, now known as “combat stress" or “Post Traumatic

Stress Disorder” (PTSD). The saddest

cases in WW-1 were the young men suffering from this illness who appeared to be

physically fit enough to be sent back to The Front. If they couldn’t cope and

deserted when caught they were shot for “cowardness”, but there is no record of

Goldhanger men suffering this fate.

In the 18th and

19th century when fishermen sought entertainment in the village,

Fish Street is said to have been the location for several unlicensed Alehouses. In fact, there was a

period when alehouses did not need licences, this was introduced in an attempt

to reduce gin consumption in cities like London, which had been creating even

greater problems of alcoholism. Some of the cottages built right on the

roadside in Fish St and Church St had shutters on ground floor windows as

protection from the drunken fishermen using the local ale houses, these can be

seen in some early photos. So vandalism, alcohol related injuries and

illnesses must have been a problem. Dr

Salter’s diary makes various mentions of drunken brawls in the streets at

D’arcy and Tollesbury at the turn of the century (HS).

With many of the poorer families

having large numbers children, and with a lack of maternity and emergency

medical facilities, there must have be a much higher death rates in the past

during birth of both mothers and babies.

Strangely, a paper in the

Lancet of August 1900 written by a Witham doctor George Melmoth Scott,

identified that Cancer rates on the Essex coast, including Goldhanger, were

lower than the national average. Tollesbury had the lowest death rate of all.

The author attributes this to number of rivers and marshes in the area, and

suggests that the clay content and alluvial matter of the water could be

responsible.

In Victorian times and until

the second world war, virtually all men smoked and many of the diseases now

recognised as smoking related, such as Emphysema, Bronchitis, lung Cancer,

heart disease etc. were not recognised for what they were, and many premature

deaths would have resulted.

Accidents

With little or no emergency

services available in the area, or a general knowledge of basic lifesaving

procedures that today might save lifes, many more accidents in the past would

have resulted in a fatality or permanent disability. Several incidents of

drowning and near drowning in the estuary have been recorded in newspaper

reports over the years from weather, shipping, fishing and swimming related

accidents.

The Great Tide of 1736 destroyed parts of the

Goldhanger seawall, swamped decoy ponds and caused in the death of five

Goldhanger men.

In 1875 Dr Salter wrote:

“Sent for in a hurry to Goldhanger.

A boat capsized and one of its occupants was reported drowned, but by four

hours diligent perseverance of artificial respiration and rubbing I got him

round”(HS). In 1885 he recorded: “Attended an inquest on a man who had

swallowed some sheep dip in mistake for beer”.

Form The Royal Humane

Society Awards, Case Number 42,487:

May 1916, The Creek,

Goldhanger. Frank Butcher, Age 16, got out of his depth when bathing in the 7ft

tidal Creek. Richard Phillips, Age 18, went in from the other side, swam over

to effected the rescuer. The Case submitted by the Revd. Field of Goldhanger.

It is on record that in the

early 1900s Mrs Ethel “Poppy” Gardner, the Rector’s wife, had accident with an

diesel electric generator in the Rectory cellar and lost an arm and in the same

period a young boy of the Page family died after falling out of a tree in the

garden of the Old Rectory.

Farm machinery and farm

animal related accidents have always been a hazard in rural communities and

would also have been more frequent, with more severe outcomes, in the past. As

recently as the 1970s a young man from the village was electrocuted and killed

when the tractor with a fork-lift attachment he was driving hit overhead power

cables that ran across a local farmyard.

Windmills and steam mills

were particularly venerable to fires and accidents, and the Goldhanger mill would have been no exception. Owners

and workers could easily take too high a risk in high winds and the dust caused

breathing difficulties. The dust and sparks from the rotating parts also

started frequent fires and many mills were burnt down. It is not know what

brought about the end of the Goldhanger windmill, but fire was the most likely

cause.

With no local fire brigade,

and no large manor house or stately home in the vicinity to support any form of

emergency cover, which was frequently the case in rural areas, chimney fires

and house fires must have been a major problem, particularly with so many wood

and “lath & plaster” cottages, perhaps built this way because of the lack

of a local stone. In 1919 the Parish Magazine(PM) reported there had been a

fire at the Parsonage. “The Rector wishes to thank all the kind and energetic

helpers who extinguished the fire at the Parsonage on the night of November

5th, but for whom the house would have been burnt to the ground, and to whom

there is still a further recognition of their kind services forthcoming”.

Advances in

public health standards and knowledge

Ignorance of disease

carriers and the transmission routes was a major factor in the spread of

epidemics the past. Until the mid 1800s, the “Miasma theory” was generally

accepted, which was the notion that diseases were transmitted by bad smells in

the air (PH).

The Public Health Act (which

Cuthbert William Johnson of Heybridge

had a large influence, see above) was introduced in 1848 and in 1854 Cholera

epidemic in London led to the discovery of a contaminated water pump in Soho.

In 1856 the “Great Stink of London” resulted in the beginning of sewage

construction. The 1880s saw the first appointments of local medical officers of

health and their resulting annual reports (PH). Dr Salter was the local medical

officers of health.

Until the 20th century there

was a general lack of understanding of basic food hygiene at all levels of

society. In Goldhanger there were two farms right in the middle of the village

up until the 1950s, and a large number of farm animals would have been right in

the middle of the village: horses and donkeys for transport, cows, pigs, sheep

for milk and meat and clothing. This meant that the disposal of animal waste

was probably perceived as a much greater risk and a concern than the disposal

of human waste. Manure heaps at the roadside were always very common (PH),

which was spread on the fields in winter. Most villagers kept pigs and chickens

at the bottom of their gardens to recycle food waste and the manure produced

was put directly onto the vegetable patch.

Before the creation of the

welfare state and the National Health Service, the general health of the

community was inseparable from poverty and unemployment. In her book Goldhanger - an Estuary Village Maura Benham(MB) wrote …

“A measure of the poverty

in Goldhanger can be taken from the records of the Hearth Tax of 1671. Of the

forty-nine names entered, nineteen were excused as too poor, a high proportion

compared with Little Totham where twenty were to pay and only two were excused

as too poor.”

Miss Benham also identified

the existence of a poorhouse in the village in the 19th century with

eleven residents, evidence that the community accepted some responsibility for

looking after the poor and infirm at that time. Early Church warden accounts for Goldhanger (ERO) refer to the distribution of

“apabs”, which is a Latin abbreviation for food.

The Goldhanger Friendly Brothers is based on an

early form of mutual sickness benefit and life assurance and was another way of

helping local poor and unemployed people before national schemes was introduced

which was unique to the village. The Friendly Brothers were originally

associated with the Wesleyan Chapel and it had other names over its 200 year

history, including “The Friendly Society” and “The Good Intent”. The Goldhanger

Friendly Brothers still meet today, although since National Insurance and

unemployment benefit were introduced in 1911 it has become largely symbolic. There

are also many records of bequests to the poor and charities being established

under the terms of the Wills of wealthy land owners in the locality.

Finally and perhaps

surprisingly, these early photos showing children in the streets show the

conditions in the village at the beginning of the 20th century. The

children appear to be well nourished, and clothed, and maybe by today’s

standard appear to be over-dressed, which contrasts with many early photos

taken in inner-cities at the same time.